GRAIN SCOTCH WHISKY

INTRODUCTION

To the uninitiated, grain whiskies are the filler in blends, knitting together the real flavour from the single malts and – since they’re typically cheaper to make – keeping the price down. True, but only partially so. Apart from giving real flavour and texture to blends, well-made grain whiskies have a distinct character all their own.

Single malts get the headlines, but they almost certainly wouldn’t exist without grain whisky – essential to the creation of the blended Scotch brands which are the backbone of the industry. The vast majority of grain whisky goes into blends, but there are a small but growing number of specialist grain bottlings.

SINGLE GRAIN SCOTCH WHISKY

Single grain whisky is defined by its single distillery manufacturing process. A whisky must be made by a single distillery in order to qualify as a single grain whisky. Single grain, regardless of the name, can be composed of one or more grains – that may not be malted or unmalted barley, creating a light-bodied and mellow taste for whisky lovers to enjoy.

To be recognised as a single grain, a whisky must be made from a single grain or blend of grains at a single distillery. This technique can employ malted or unmalted grains, but it is not confined to that. A grain whisky employs additional malted or unmalted grains in the mash, rather than mostly malted barley. If a single grain whisky is classified as Scotch, it must be matured for at least three years as it happens with any other types of Scotch Whisky.

It is essential to remember that the term “single grain whisky” refers to the number of distilleries, not the number of grains that can be utilised. The laws do not specify the size or shape of the still. However, this type is commonly distilled in a Column or Coffey still rather than a pot still.

To avoid using artificial enzymes, most distillers utilise at least 5% malted barley, which allows enough amounts of natural enzymes to be introduced, easing the fermentation process. In other words, grain whisky is made by cooking up unmalted cereal grains – corn, wheat or maize, but typically wheat these days – and then combining them with some malted barley to help kick-start fermentation.

Distillation is carried out using the continuous patent

still process, a method pioneered and refined in the 19th century. Apart from

the obvious efficiencies of this being a continuous process – in contrast to

single malt distillation, which happens in batches – the aim here is produce a

spirit high in alcohol and light in character. At cask-filler strength, it is not potable and requires maturation in oak casks, no matter how old.

The rules governing Scotch whisky production stipulate that grain whisky must keep some flavour from its raw materials, and different grain distilleries – like their malt cousins – produce different styles. With practice, you can tell your Cameronbridge from your North British or your Girvan.

Bottlings from the big grain distilleries, which feed the vast blended Scotch whisky industry, have long been bottled and sold, mostly as curiosities to pique the interest of the whisky enthusiast. But things are changing.

Scotch whisky iconoclasts Compass Box’s blended grain whisky Hedonism (you can blend grains from different distilleries in a similar way to blended malts) has been a favourite for several years, while fellow blended grain Snow Grouse, unusually designed to be drunk cold, is a good introduction to the world of grain.

And now William Grant, owner of the Girvan grain distillery, has gone further by producing its own range of aged single grain whiskies, including an NAS bottling and a distinctly high-end 25-year-old. Exciting times – at last – for grain whisky.

The main feature of grain whisky distilleries is their large capacities with an average of over 50m Litres of Pure Alcohol (LPA) produced per year. In comparison, most malt distilleries are smaller with an average of circa 2.5m LPA produced per year. Scotch whisky production and marketing between the start of the Second World War (WWII) and the end of the last millennium changed and shaped the current modern whisky industry profoundly. Numerous changes took place over the past five decades, starting with WWII until the mid 1970s.

As a consequence of the WWII and the restrictions in distilling, the amount of proof gallons of malt whisky distilled decreased rapidly from 10.7 million in 1939 to nil in 1943 before increasing progressively to pre-war levels in 1949 and stabilising around 12 million between 1950 and 1954. The production volume for grain volume followed the same trends.

WWII & RESTRICTIONS:

In early 1940 the manufacture of spirits was limited to 1/3 of the quantities distilled in the year ended before September 30th. This was to ensure food supplies for the British population. Patent (grain) distillation virtually ceased in 1940. The malt distilleries were limited to 1/3 – 10%. In 1944, distilleries were allowed to resume production to 1/3 of the 1939 volumes.

In addition, to the reduction of production, several distilleries were bombed [e.g., Banff and Caledonian (Cally) distilleries] resulting in estimated losses of 4.5 millions proof gallons, the equivalent of 1 year of war production.

Once the largest distillery in Scotland, Edinburgh's ‘Cally’ produced grain whisky from a Coffey still, as well as two large pot stills. Covering five acres of land, Caledonian was built during a boom in new grain distillery builds – by 1857 there were 17 distilleries operating patent stills in Scotland. The boom led to oversupply, but Cally rode the tide. The distillery also produced an Irish-style grain whisky distilled in two large pot stills, a style revered among blenders at the time for its consistency. It was shut down in the 80s.

Some old parcels of Caledonian have been bottled as a single grain by indie bottlers in recent years. It has never been bottled as a single grain, save for a commemorative bottling for the 1986 Commonwealth Games held in Edinburgh, while Diageo released a 40-year-old, 1974 vintage under ‘The Cally’ label, as part of its 2015 Special Releases.

POST WAR

While close to 50% of the whisky was consumed at home, the situation changed markedly afterwards. Great Britain was in need of money to pay for their loans accumulated during WWII. Therefore, they decided to increase duties at home, to reduce home consumption and to push the industry towards export. Once the taste of whisky was experienced in Europe by US soldiers through , the US became rapidly the major export market for Scotch whisky. In 1947, the percentage of home-consumed whisky was 45.3%, but dropped to 30.1% the next year and remained at ~ 25% until 1954, decreasing only slightly afterwards (down to 20% in the 1970s. Exports of whisky (Scotch and Irish) to USA increased from 2.8 million in 1947 to 7.1 million proof gallons in 1954. Volumes remained at the same levels at home, at around 8 million PG during this period. In 1970, the USA represented 42% of the world market for Scotch.

This “revolution” in whisky distribution was due to the rationing imposed by the Scotch Whisky Association between 1940 and ’45, before being phased in gradually up to 1953. Restrictions were lifted on 1st January, 1954. During the post-war period, USA was by far the major export destination for Scotch, with Europe showing promise. Europe remained a complicated and challenging market, since each country had its own restrictions.

As a consequence of the WWII and the restrictions in distilling, the amount of PG of malt whisky distilled decreased rapidly from 10.7 million in 1939 to nil in 1943 before increasing progressively to pre-war levels in 1949 and stabilising around 12 million between 1950 and 1954. The production volume for grain volume followed the same trends. This led to an insufficiency of fully matured whisky to meet demand.

Construction of new distilleries took place mainly in the 1960s, with Invergordon and Girvan distilleries featuring prominently. A consequence of increased output was a shortage of sherry casks. More American casks were thus imported. However, the construction of warehouses lagged behind. Both to save casks and warehouse space, grain whiskies began to be filled at 20° over proof instead of 11°, thus allowing to increase storage capacity of 8%.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MALT AND GRAIN WHISKY

As with single malt whisky, the word “single” in the name indicates that it is also the product of a single distillery. However, and here’s the main difference between them: single grain does not have to be exclusively manufactured from barley or malted. On the other hand, single grain whiskies are frequently manufactured from wheat, maize, or a combination of the two.

| ||

| MAP OF GRAIN DISTILLERIES IN SCOTLAND | |

Cameronbridge, owned by Diageo, is the oldest (1824) and largest grain whisky distillery producing over 110m LPA per year. It was also known as Haig Distillery in the past. As part of their production expansion at this site, Diageo closed their Port Dundas grain distillery in Glasgow in 2010.

North British, a joint venture between Diageo and The Edrington Group, was established in 1885 and until a few years ago it used to be the 2nd largest grain whisky distillery producing around 72m LPA per year. It historically only used maize as the main cereal.

Girvan, owned by William Grant & Sons, was built in 1963 and it also produces malt whisky at its nearby Ailsa Bay distillery (2007). Since 2007, it has increased its production capacity by 50m LPA, and it is now the 2nd largest and comparable to Cameronbridge, producing over 100m LPA.

Starlaw, owned by La Martiniquaise is the newest grain distillery, founded in 2010. It produces 25m LPA per year.

Strathclyde, owned by Pernod Ricard, was established in 1927 and produces around 40m LPA per year.

Loch Lomond, owned by the Loch Lomond Group, is the smallest grain whisky distillery producing around 18 LOA per year and it was introduced to the site in 1994. The Loch Lomond distillery also produces malt whisky and until the opening of Ailsa Bay in Girvan, it was unique in producing both grain and malt whisky on the same location in Scotland. One unusual feature is that one of the stills used at Loch Lomond Distillery (graphically represented below) is a Coffey/ Continuous still, with copper on the inside and producing Scotch whisky only with malted barley. This would be a single malt if it was not for the continuous distillation on process, rather than batch, and therefore it is called a single grain scotch whisky. The product is called Loch Lomond Single Grain Scotch whisky

To be known as ‘Scotch whisky’, a mash of cereals, water and yeast must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of three years in oak casks.

There are two main types of whisky produced in Scotland: malt whisky and grain whisky. All whisky begins its life as the product of a ‘single’ distillery – so these products are known as ‘Single Malt’ or ‘Single Grain’. No second or sister distillery may feature in this Single category.

Single malt whisky is made in a traditional batch process using a copper pot still. According to the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009, to be classifed as a Single Malt Scotch Whisky it must be "produced from only water and malted barley at a single distillery by batch distillation in pot stills".

Single malt is the premium, traditional style of whisky, but the artisanal manner of its production is not easily scaled.

The production of single grain whisky is very different. Unlike single malt, it can be produced from a variety of different grains or cereal types, either malted or unmalted. Single grain whisky is also made continuously via a modern column still, on an industrial scale. The output is purer in alcohol, but with much less flavour and character than a single malt. It is also very much easier to produce.

The overwhelming majority of Scotch whisky consists of malt and grain whiskies mixed together to make a product known as Blended Scotch whisky. Blends have dominated the Scotch industry for over a century, and continue to do so today. In 2020, Blended Scotch whisky accounted for 62% of exports by value and 83% by volume. While bottled single malt Scotch is a rapidly growing category, it still falls behind, accounting last year for only 15% by volume and 36% by value of all Scotch whisky shipped overseas.

By law, the age statement shown on a Scotch must refer only to the youngest whisky included in the product – meaning that all malt and grain whiskies included must be at least as old as the age shown on the bottle.

Most Scotch is bottled between the ages of 3 and 12 years. Three years is the minimum age for a spirit to be classified as 'Scotch whisky', and many ‘value’ products, such as supermarket own-label blends, will likely consist of whisky at this age. At the same time, Johnnie Walker Black Label and the youngest Chivas Regal, which account for 10% of all Scotch sales worldwide, are both 12 year old whiskies.

The most important fact about malt and grain whisky is that they are both components of the same finished product – blended Scotch. As commodities, however, there are a few differences between malt and grain which are worth considering.

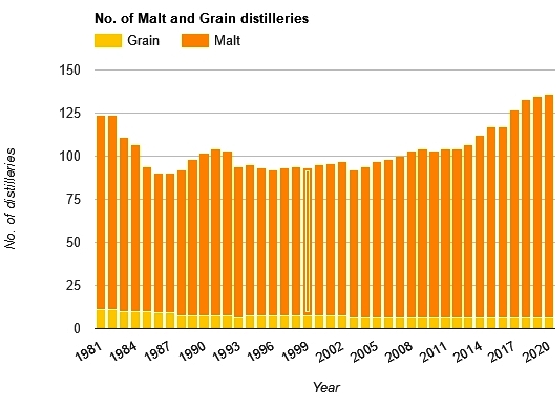

More grain whisky is produced than malt – but far fewer distilleries make it. The radically different methods used to produce malt and grain whisky mean that there are huge differences in the production capacity of the distilleries which make them.

There are currently 130+ active malt distilleries, and 7 active grain distilleries. The largest malt distillery, Glenfiddich, can produce 21m Litre of Pure Alcohol (LPA) per annum, while the smallest, Dornoch, can only make 0.02m LPA in one year.

These figures are dwarfed by those of grain distilleries. The largest grain distillery, Cameronbridge, can produce up to 110m LPA of whisky each year. Even the smallest grain distillery, Loch Lomond, produces 18m LPA – almost as much as the largest malt distillery, Glenfiddich.

Despite the fact that there are ~ 19 malt distilleries for every grain distillery, Scotland normally produces more grain whisky every year. The price of grain whisky is generally more homogenous than malt

For both new malt and new grain spirit, the distiller's selling costs are historically far more closely related to the costs of utilities and grain required for production than the selling prices of the finished product.

Grain whisky is far cheaper to produce than malt whisky. Historically, the price of new make malt spirit has been more than twice that of grain spirit, per LPA. (These prices do not include the cost of wood.)

Due to the low number of grain distilleries, it is

easier to manage the production of grain whisky than malt whisky. In periods of

over-production, the taps are, quite literally, turned off, or else, diverted as ethanol to mainstream industries, mainly pharma.

This is more difficult with malt whisky, due to the higher number of distilleries – and distillery owners. In the early 1980s, this caused a delayed reaction to slowing worldwide demand for Scotch, which was ultimately only resolved by a raft of malt distillery closures.

Today, however, two producers – Diageo and Chivas Brothers – own distilleries with a total capacity of 187m LPA – nearly half of the total full capacity of 395m LPA in Scotland. Distillers have also become better at forecasting future demand levels. This has reduced the danger of high-level over-production, like that of the 1980s, re-occurring.

More grain is used in blends than malt – and often at a younger age. In a blend, grain provides the bulk of the body of a blend, while malt provides the more complex flavours. For this reason, malt whisky used in a blend is often older than the grain used. The typical bottle of blended whisky is 70% grain, 30% malt. More premium offerings may include a higher percentage of malt.

As few distilleries produce grain whisky, and as the spirit which they all produce is relatively homogenous, there has not historically been a significant variance in the price of grain whisky at the same age from different distilleries. This is not the case for malt, where prices for whisky from different distilleries may vary more widely.

|

|

|

|

|

SINGLE GRAIN WHISKY TASTE

Single grain whiskies are often light-bodied and mellow, making them an excellent introduction for those who just now entering the whisky world. Corn, maize, wheat, and old barrels are commonly utilised. Add in oak maturation, typically in first-fill former Bourbon casks, and you have a gentle, often fruity and sweet whisky which at its best acquires a refined, velvety character as it ages.

Since this type of whisky is made from corn, maize,

wheat and aged in older barrels, their character is somewhat sweeter than

single malts, for instance. Contrarily to the bourbon flavour – that is made

with 51% corn within the mash – the single grain expressions do not have the

smoky flavours, the maple or vanilla flavours one can find in conventional

bourbon whiskey.

THE GRAIN WHISKY MARKET

Historically, the single grain whisky category was not something that was bottled and marketed. It was and still is predominantly utilised in the production of blended whiskies such as Dewar’s White Label, Johnnie Walker Red, and Jameson, to mention a few.

It is easier and less expensive to make than single malt, which is made in batches. Single grains can create a high-quality blended whisky at a very reasonable price when mixed with single malts. Historically, the single grain whisky category was not something that was bottled and marketed. It was and still is predominantly utilised in the production of blended whiskies such as Dewar’s White Label, Johnnie Walker Red, and Jameson, to mention a few.

It is easier and less expensive to make than single malt, which is made in batches. Single grains can create a high-quality blended whisky at a very reasonable price when mixed with single malts. The single grain category has gained popularity in recent years, with whisky companies producing some excellent whisky expressions.

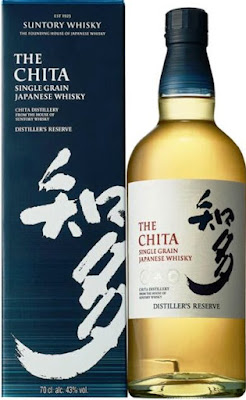

If I were to be asked to nominate one single grain whisky, I'd go beyond the scope of this article for the Japanese Chita. I found it superior to all Scotch Grain whiskies. C'est vrai.

ADDENDUM:

The Chita Single Grain Whisky is the only grain whisky

produced and bottled as such by Suntory. It is a blend of single grains (mainly

corn), relatively young, but with strong tasting characteristics that have been

aged in different types of casks, and distilled at the Chita distillery, a few

kilometers from Nagoya city.

Its rich and complex aromatic profile is strongly

marked by fruity, woody and spicy notes, closer to American Bourbon than Grain

Scotch whiskies.

Bottled at 43% of the volume in a bottle with the

typical Suntory shape, The Chita is a tribute to the know-how of the grain

distillery whose name in traditional Japanese calligraphy is now, like the

other distilleries of the group, proudly displayed on the label.

Founded in 1972 in Aichi Prefecture, Chita distillery,

located near the village of the same name, covers an area of approximately

50000 m² and is exclusively dedicated to the distillation of grain whisky. Like

its two distilleries of malt Yamazaki and Hakushu which are capable of

producing several types of single malts, several varieties of single grains are

produced there.

The Chita can be enjoyed at room temperature with or

without ice to express all its taste palette, or in highball for a refreshing

and 100% Japanese tasting experience. The Chita Whisky is also blended with

malt from Yamazaki and Hakushu to make the illustrious Hibiki.

THE DISTILLERY

Founded in 1972 by Keizo Saji, the son of the founder

of Suntory, the distillery was established on the shore of the Chita peninsula

to produce the grain whiskies of the brand's blends.

Equipped only with column stills in which it distills

mostly corn, the Chita distillery today has a unique expertise enabling it to

produce single grain whiskies and bottle them as such.

Using a continuous multi-column distillation process,

Chita can produce three different types of grain whiskies; a strong one

distilled through two columns, a medium one through three columns, and a light

one through four columns.

All three spirits are used in The Chita, blended with a

recipe created by Keizo Saji, the second Master Blender of Suntory, by current

Master Blender Shinji Fukuyo. He wanted to create a whisky that reflected the

Japanese craftsmanship and nature. The Chita is matured in three different

kinds of casks: American ex-bourbon barrels, Spanish Oak barrels and European

Oak wine barrels. This NAS whisky is bottled at 43% ABV (86º proof).

The distillery does not have its own ageing cellar, so

after distillation the barrels are transferred to two sites with unique natural

climatic conditions; Omi and Hakushu. Like American bourbons, the vast majority

of Chita's grain whiskies are aged in American white oak barrels.

Today, the know-how accumulated over the years is

expressed through a grain whiskies that pay tribute to this great distillery.

With The Chita, Japanese whisky takes on universal accents while keeping that

Japanese touch that makes all the difference.

Tasting Notes:

Appearance: In the glass, the whisky is straw-colored

and has medium legs.

Nose: On the nose, it is smooth and fresh. The Chita

Single Grain is a floral whisky with notes of fresh fruit. There is a nice

touch of lemon that blends with mango, banana, and pears. There are also some

vanilla and caramel notes, mixed with a soft spicy touch.

Palate: The Chita is mellow and has a medium body.

Smooth and light, its fruitier side slowly comes to the forefront on the palate,

blossoming into a velvety sweetness. There are intense mango and banana notes,

balanced with a sweet touch of vanilla. Then the honey takes the lead and mixes

well with the spices. There is a slight touch of cardamom that joins the final

oak notes.

Finish: The finish is intense and longer than expected.

Some vanilla and fruit notes remain on the palate, with a light spicy touch.

Overall: The Chita Single Grain whisky is a fresh and

well-balanced whisky, as good as other Suntory whiskies. Sweet and fruity, it

shows the typical notes of a great Grain Whisky. It is a perfect whisky for a

summer evening, able of showing different layers and nuances.

The Rest: NAS, 43% ABV, RRP£52.50/€50 to €55/$60