CHIVAS REGAL 12 YEARS OLD

In 1854, at age 44, James met and married Joyce Clapperton. They had four children, Julia Abercrombie, Alexander James, Williamina Joyce and Charles James. When James died, his Will stipulated that his wife and all four children be given £ 5,000 each. To their horror, they found this impossible due to lack of money and settled instead for a monthly packet of £ 100 each for five years, overcoming stiff resistance by the shiftless Charles James who had met and married one Emma Grosskopf in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA.

The last actively connected Chivas family member, James' son Alexander Chivas, died in 1893, and control was handed over to two temporary directors, Messrs Smith and Taylor, while matters were resolved in the incredibly haphazard, dishonest and unscrupulous market of Scottish/ Scotch whisky. For example, there was no statute on the age factor of Blended Whisky, forcing customers to rely entirely on the vendor’s statement. The first ever law on such age statements started as The Immature Spirits (Restriction) Act 1915, which required the ageing of both grain and malt-based alcohol in barrels for at least 2 years in a Bonded Warehouse, quickly extended to 3 years later that same year, while charging holding taxes on a quarterly basis.

The business continued to expand with time, and 49 Castle Street replaced the smaller premises at 47 Castle Street. In 1837, Edward, seeking even larger quarters to house his newly added retail and service placement businesses, moved uptown to a fashionable location at 13, King's Street. James Chivas, hired in 1838, rose to minor partner that very year, with almost total control over the wines and spirits department, as Edward was struck with a 'palsy' and died overseas just three years later in Madeira in March '41. As Edward had died intestate, his legacy went under judicial probate. In this indistinct period for business out of those premises, James left and joined a similar victuals provender, Charles Stewart as junior partner, registering themselves as Stewart and Chivas, 39 Woolmanhill Street. They bought the vacant 13, King Street property available post-probate later that year and relocated there as a “One-stop-shop.”

James Chivas remained the sole common partner/owner till his death. The company, when known as Edward and Chivas (1838-41) and later Stewart and Chivas (1841-57), had furthered the ex-Forrest company's reputation for excellence from the extravagant shop at 13 King Street and obtained a Royal Warrant to supply luxury goods to Queen Victoria in 1843. Between 1843-51, they expanded further and added 9,11 and 23 King Street. James purchased 21 King Street as his residence.

The Forbes-Mackenzie Act permitting vatting of whiskies when in a bonded warehouse was passed in 1853, with a proviso that the bonded warehouse would be no further than one-quarter mile from a town. A larger variety of blended malts were now available to vendors to sell. Initially open to selling outsourced Blended Malt whiskies that met their stringent quality standards, they moved up to blending, ageing and selling proprietary deluxe malt whiskies starting in 1854.

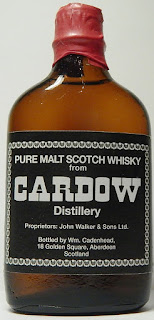

Privy then through Andrew Usher—a major brewer but small-time distiller and sales agent for George Smith's The Drumin Glenlivat (sic) of King George IV's 1822 demand fame, who had outreach into the corridors of power—to PM Henry J Temple’s tacit approval of his Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone's plan to permit the blending of malt and grain whisky in bond by 1860 under the Spirits Act (often called the Scotch Whisky Act of 1860), James started to secretly blend malt and grain whisky as suggested by Usher and requested by his customers, aiming to create a proprietary aged blend by 1860. This Act, when published, was surprisingly limited to distillers and brewers only, benefiting Usher but not James. It took a further three years till grocers could carry out the blending of such "spirituous liquors" in Bond on-premises and sale under their own label legally, under an Extension to the tariff-related Anglo-French Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860. In this period, many other grocers and wines & spirits merchants got set to enter the business full-time—John Walker, George Ballantine, Peter Thomson of Beneagles, William Teacher and the Berry brothers are good examples. Matthew Gloag of the Famous Grouse was to follow much later.

From 1864 spirit strength could be reduced using water in approved warehouses, and 1867 saw the bottling of whisky for domestic consumption in bonded warehouses. The blending boom, which would really take off during the 1870s, was a growing interest in malt whiskies distilled in what is now called the Speyside region of production in north-east Scotland, specifically an 80 sq miles tract lying between Tomnavoulin and Ballindaloch that was usually referred to in the 19th century as ‘Glenlivet.’ Their favourite whisky was Scotland's first Single Malt, GJ Smith's The Glenlivet. This brand soldiered on as it was found too mild in an era of heavy,complex and dense Blended Malt.

- Magna Charta Blended Malt Scotch, 5-Year-Old (initially outsourced, but bought in 1858).

- Royal Glen Dee Blended Malt Scotch, 6-Year-Old (in-house).

- Royal Glendee Blended Malt Scotch, 8-Year-Old (in-house).

- Chivas Old Vat Blended Malt Scotch 5-Year-Old which had replaced in 1895 the outsourced and then acquired in 1858 Magna Charta and was made with better malts.

- Royal Glen Dee Blended Malt Scotch 6-Year-Old, but allowed to fade out in 1885.

- Royal Glendee Reserve Blended Malt Scotch 8-Year-Old, improved by blending some of the select malts used for the fading 6-Year-Old which had now aged two years more with better malts from the wider range available.

- Royal Glen Gaudie Blended Malt Scotch 8-Year-Old, Master Blender Charles Stewart Howard's- ex J&G Stewart- first contribution, blended in 1894 at 48% ABV and targeted at the local market and then at the promising market in Australia: Popular in Australia.

- Royal Strathythan Blended Scotch 10-Year-Old: Popular in the US and Australia.

- Royal Loch Nevis Blended Scotch 20-Year-Old: Very popular in the US.

Chivas Regal Blended Scotch 25 YO met with resounding success. Ironically, no member of the Chivas family had, or would ever have, any connection with this ultra-premium successful blend, or, for that matter, its substitute in later days, the 12 YO. The basic price was a steep 38 shillings per gallon, eight more than that of Royal Loch Nevis and 15 more than The Glenlivet 12 YO, which was destined to become USA’s leading Single Malt after WW II. It was all one-way street for the Chivas Regal, from 1909 till end 1914, when WW I started to become a sluggish long drawn affair (1914-18). Existing stocks were exhausted quickly as demand outstripped supply. Shipping lanes to the USA closed down and Chivas Bros switched to building reserves at home.

The surviving partner William Mitchell, unable to handle Chivas Brothers, sold off the entire holdings to whisky brokers Morrison & Lundie in 1936 on an 'as is' basis. Well stocked, Morrison decided that it was far too onerous to maintain aged barrels of whisky. They wound up the Loch Nevis and reduced the production of the Chivas 25 drastically, resulting in its withdrawal as their standard-bearer and ultimate demise. They disposed off most of the aged stock in a greedy market to recover their cost of investment in no time. Morrison & Lundie sold the Chivas Brand for just £85,000 to Canadian Samuel Bronfman’s (1889-1971)Seagram Limited Company, who switched his attention to a 12 YO premium brand, a decision that would be seen as wise a lustrum later, when WW II (1939-1945) broke out in Europe, 4,000 miles from the USA. 1939 saw the debut of Chivas Regal 12 YO in the USA at what was to become a global standard proof value of 75°, i.e., 42.8% ABV (86° proof in USA).

Bronfman was on the lookout for a distillery as a home base. His agent found one in 1950 called the Milton(aka Miltown) Distillery at Strathisla, Keith. The owner, one George (Jay) Pomeroy, a known scoundrel, wanted an astronomical sum, so Bronfman backed off. But the owner was jailed that year for fraud and Milton (aka Miltown) Distillery was put up for auction. Seagram purchased Milton for £71,000 at a public auction in Aberdeen in April 1950. This purchase was the second time Milton Distillery had changed hands in a public auction.

Bronfman changed its name to Strathisla, as its water came from the river Isla, pronounced exactly as the peat haven of Islay. He had unknowingly struck gold as Strathisla distillery housed a vast amount of ageing whiskies underground, both malt and grain, mainly the Strathisla Old Highland Malt Whiskies, and another warehouse beneath the Glasgow railway yard, all between 6 & 10 YO. He then needed a good Master Blender and hijacked the Master Blender of J&B, the preeminent Charles Julian, who revealed that with the huge quantity of whiskies available at his new home, he could produce a superb 12 YO, only by 1954, but in great and annually repeating volumes. This was kept secret since Bronfman wanted to make headlines with the first deluxe 12 YO Scotch whisky after the War. Seagram employees were made to feel that Bronfman, an overly dynamic, brash and irascible man, seemed to be at odds and ends, juggling various whisky brands to keep the cash flow alive.

In the spring of 1954 and after an absence of over five years in the marketplace, Distillers Corporation-Seagrams Ltd. rolled out in grandeur the Chivas Regal 12-year-old Blended Scotch Whisky in the United States. This also kept British authorities happy with export income. Chivas Regal 12 YO sold at $8.00 per 750 ml bottle, vs the $3.5-5.0 for lesser whiskies in the 'fine' and 'rare' categories. It was also sparingly sold in the UK soon thereafter.

Bronfman’s shrewd philosophy of sale was an artificial creation of a shortage: The early advertising strategies devised by Sam Bronfman and his team for marketing and promoting Chivas Regal was to create the illusion of overwhelming demand for Chivas Regal in a time of acute shortage. “What assets do we have? Its [Chivas Regal] label is terrible but seems genuine. We have a Royal Warrant, and own one of the oldest operating distilleries in the Scottish Highlands, but to what avail? Only time will tell.” This was the initial refrain making the rounds in both the USA and the UK.

In the USA 1953-54, Sam’s advertising agency created and ran multi-page, full-colour ads in upmarket magazines and key trade publications. The flashy inserts heralded the coming of Chivas Regal. Full-colour free booklets that told the Chivas Regal story were sent to thousands of intrigued consumers across the country. Sales staff were to tease distributors by selling them only small amounts of Chivas Regal when it came, thereby instigating an instant “shortage” as soon as Chivas Regal hit the streets, a brilliant move. Bronfman wilfully told distributors, salesmen and retailers that there would never be enough Chivas Regal. He wanted them to get a fast turnover and come back for more. People always wanted what they couldn’t get.

He wrote to 200,000+ moneyed men, “As a connoisseur in this class, I urge you to visit your pub or spirit shop and to ask for a bottle of Chivas Regal, which, though very limited in quantity, will be reserved for you, who appreciates the best in Scotch whisky.” His ad agency devised a series of “shortage crisis” print ads disclosing the deficit situation of Chivas Regal. Consumers were asked to show ‘patience’ while more Chivas Regal was being produced and matured across the Atlantic and their wait wouldn’t be overly long. All such statements were patently false, a shrewd marketing strategy.

The “CR shortage” strategy worked better than expected. Distributors quickly ran out of Chivas Regal and immediately reordered, but were then only given another carefully meted out case amount. Retailers placed Chivas Regal on strict allocation exclusively to their best, most affluent clientele because “The best people in town were talking about Chivas Regal. . . . Styles start at the top and percolate downward...” The perceived, if hollow, scarcity snowballed into a minor feeding frenzy for Chivas Regal in the major US markets throughout 1954 and 1955. The backbone single malt in the Chivas Regal family was the Strathisla, buttressed by Glenlivet and rounded off with Braeval and Longmorn. Other malts were added to maintain consistency in flavour and taste.

Bronfman decided to finance Chivas as its whisky and gin producing arm, with the Chivas Regal 12 YO Blended Scotch Whisky bringing in the money from across the globe, bar the Middle East, soon to become a new and growing oil-spawned market. Since Bronfman was Jewish, the Seagram brands, including Chivas Regal, were not seen in the Middle East until 2001 and firmly under Pernod Ricard patronage. Phipson's Black Dog 12 YO Blended Scotch, an 1889 product that ruled the roost over the Australasian half of the British Empire up to 1983 gave way to Haig's Dimple 12 YO, and Diageo's Johnnie Walker Black Label thereafter.

In the next 25 years, Aberlour, Glenallachie, Edradour, The Glenlivet, Glen Grant and Longmorn distilleries were brought into their fold by Seagram. Benriach joined its fold for just two years and was hived off as it was found complex for Chivas' classic style of blending.

Their prize catch was a controlling stake in The Glenlivet Distillers Ltd in 1978, for which Edgar, the eldest son of late Samuel Bronfman paid £46 million (~ $88 million at the time). Its sister distillery Glen Grant was also acquired, allowing him to aggressively market a 5 YO Glen Grant in Italy and simultaneously insert Chivas Regal into that market. The valuable lessons learnt when promoting the Glen Keith malts assisted Strathisla product 100 Pipers in the USA to counter the Cutty Sark and J&B Rare were employed here.

Today, Seagram is part of Pernod Ricard and Chivas Brothers is the second-largest Scotch whisky company after Diageo. This perplexing statement reflects how fortunes fluctuate in the liquor industry.

In 1994, Edgar Bronfman handed over control to his eldest son, Edgar Jr who had little interest in whisky, preferring the glamour of the cinematic world. He led Chivas Regal into almost total ruin with a series of appalling decisions, despite sane advice to the contrary. His worst experiment ever was the “Chivas DeDanu,” a specially concocted blend geared for younger drinkers in Italy. It failed on Day 1. To the shock of old-time Seagram money managers the world over, the dim-witted Edgar Jr sold their entire blue chip 24% Du Pont holding in 1995 at a price 13 % lower than the market rate. Commentators said, “Buying Du Pont was the deal of the century; selling it was the dumbest deal of the century.”

The epigram "from shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations" was proved.

He moved the excellent Something Special 12 and 15 YO Blends out of Asia into South America, where it rose immediately to No 1, later settling as No 3 when the Something Special 12 YO went NAS. In his mind, entertainment was “in” and booze was “out.” He spent $5.6 billion on MCA Inc., which made movies and operated theme parks. In October 1999, he along with Jean-Marie Messier, the blustery top manager at Vivendi, the French water and utility firm, formed a dubious bond that would on December 8, 2000, resulting in the ill-fated union of Seagram and Vivendi. Edgar traded the family’s controlling stake in Seagram for what amounted to less than 9% of Vivendi and the two giant companies evolved into a single corporate entity, the Vivendi Universal. In August 2002, Vivendi Universal went bust and Bronfman was on the street, easy pickings for Pernod Ricard S.A. of France and Diageo plc of the UK. It retained its name, Chivas Brothers, as promised almost a century ago.

- Aberlour: Speyside Single Malt (SMS) Scotch Whisky

- Allt-a-Bhainne: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Braeval: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Caperdonich: Speyside SMS Whisky (Glen Grant No. 2), mothballed in 2002. Still provides very old single malt whiskies, though.

- Dalmunach: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Glen Keith: Speyside SMS Whisky, which also produced the double-peated Craigduff SMS Whisky, never released as a distillery offering. Chivas insists, however, that Craigduff was made at Strathclyde.

- GlenAllachie: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Glenburgie: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Glentauchers: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Longmorn: Speyside SMS Whisky. Key component of Chivas Regal and Something Special. Something Special was very popular in India, and Chivas Bros, sensing a potential conflict with Chivas Regal, had Seagram move Something Special out to South America in 1980, where it met with instant success.

- Miltonduff: Speyside SMS Whisky, key component of Chivas Regal. Also produced Mosstowie SMS Whisky.

- Strathisla: Speyside SMS Whisky, key component of Chivas Regal.

- The Glenlivet: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Tormore: Speyside SMS Whisky

- Strathclyde: Lowland Single Grain Scotch Whisky, key component of Chivas Regal.

- Glenugie: Highland SMS Whisky, shut down in 1983, but provides diminishing stock of very aged whiskies for the 30-YO plus category, like Chivas Brothers’ Deoch an Doras range and Royal Salute 32, 38, 50 and 62 YO.

- Scapa: Islands SMS Whisky

In view of the falling sales, the Ad Agency was changed, the bottle was changed from dark green to clear glass to accentuate the striking tawny-amber colour of Chivas Regal and a new ad followed. The headline read: ‘What Idiot Changed the Chivas Regal Package?’ The copy explained the reasons (you could now see the whisky, etc, etc). Its conclusion: ‘Maybe the Idiot Was a Genius.’” This one ad turned a fading Chivas Regal into the shining star it is today.

In 1958, Chivas Brothers closed both the King Street and the Union Place shops and moved to a new retail location at 387-391 Union Street. The new site included a restaurant, called Chivas Brothers. In early 1960, a bar called the Crusader Bar was opened. The restaurant turned into a popular meeting place for well-to-do Aberdonians throughout the 1960s and 1970s. On January 31, 1980, Chivas Brothers closed down for good and has never reopened.

|

|

Though

a NAS whisky, it has often been quoted as a 25 YO and a decanter recently auctioned

by Sotheby’s was a 50 YO, distilled in 1968 and bottled in 2018, in memory of

Manchester United’s European Cup final victory in 1968. Do note that there is

no reference to the Royal Salute family, which comes from a totally disparate

genre.

THE FOUR EXTRA 13 YO LAUNCH 2020

In March 2020, Chivas launched the Chivas Extra 13 collection: a range of four 13 year old whiskies that deliver extra flavour with the addition of one of four casks during the whisky-making process: Oloroso Sherry, Rum, American Rye, and Tequila.

The new collection was inspired by pioneering whisky blenders and founding brothers James and John Chivas who imported rums, exotic spices, and luxury food items from across the globe to their emporium at 13 King Street, Aberdeen. Each additional cask brought into the maturation or finishing process imparts its own unique combination of characteristics onto the Chivas blend, bringing a number of new flavour notes to the spirit for the first time:

– Chivas Extra 13 Oloroso Sherry Cask: the selective Oloroso Sherry cask maturation delivers a richer finish, with hints of sweet ripe pears in syrup, vanilla caramel, cinnamon sweets and almonds.

– Chivas Extra 13 Rum Cask: the selective Rum cask finish delivers a sweet finish with rich flavours of juicy orange, sweet apricot jam and honey offset by warm and spicy cinnamon flavours.

– Chivas Extra 13 American Rye Cask: the selective American Rye cask finish delivers an exceptionally smooth and mellow finish, with flavours of sweet and juicy orange and creamy milk chocolate.

– Chivas Extra 13 Tequila Cask: the selective Tequila cask finish delivers a sweet and round finish, with hints of grapefruit and pineapple.

With each new expression featuring artwork by renowned street artist Greg Gossel, Chivas has once again established new boundaries of traditional Scotch whisky with a fresh approach to pack design – blending images from its history with contemporary designs celebrating each finishing cask’s vibrant heritage. The four new whiskies rolled out globally in select markets from March, with the Chivas Extra 13 Rum Cask available exclusively via travel retail outlets from July that year.

THE ULTIS & THE 25 YO

|

|

|  |

In 2016, Chivas produced their first blended malt after the 1894 Royal Glen Gaudie in the form of Chivas Regal Ultis. Ultis is presented in a snazzy bottle, housed in a snazzy box and has some snazzy marketing behind it - a story of the five master blenders who have preserved the Chivas house style since 1895.

The single malts used in Chivas Ultis are:

- Tormore: Presenting the palate with rich citrus orange notes.

- Longmorn: Revealing a creamy smooth vanilla toffee character.

- Strathisla: The heart of every Chivas whisky, full of malty and fruity charm with a subtle sweetness.

- Allt-a-Bhainne: Bringing balance in the form of spice and malt, adding subtlety to the blend.

- Braeval: Displaying a complex floral scent with green notes.

The five blenders: Charles Howard (of the first ever Chivas Regal blend, the luxurious 25 YO of 1909 fame), Charles Julian, Allan Baille, Jimmy Laing and Colin Scott (current Master Blender) are honoured in several ways with Ultis; visually, the bottle has five etched rings around the closure, as well as a giant embossed V on the bottom of the bottle; spirit-wise, five different single malts have been selected. While the actual constituents in terms of volumes and ages are not specified, it is known that all five are close to the 20 YO mark. It’s not cheap either at £170. Sadly, this is a listless 40% ABV whisky in a 70 CL bottle. It is fading into oblivion.

Chivas Regal Ultis is now history. Its successor Chivas Ultis XX is the ultimate indulgence. Every bottle contains an exclusive blend of Chivas’ rarest and most precious single malts, married with their signature single grain.

This whisky was created with five blended malt Scotch whiskies; Master Blender Sandy Hyslop made this whisky in honour of his five predecessors who held crucial roles in Chivas history, adding predecessor Colin Scott to the pathfinders. The importance of this number can be seen in the five copper rings across the bottle’s neck. Aged for 20 years, this is the ultimate blend to mark an occasion.

With less than 1% of the millions of casks within their inventory used, and each cask individually hand-selected and nosed, they have ensured only the highest quality are included in a blend worthy of a celebration.

Addenda:

British Chancellor of the Exchequer under PM Henry Temple in 1860, Gladstone was under pressure from distillers because of his Malt Tax, which depended directly on ABV. Average Malt ABV was 65%. So, under his fiat, Revenue authorities agreed to allow the blending of “plain British spirit” with pot still malt whiskey. Dealers were permitted to bring any spirit from any part of the UK (including Ireland at that point) to any other part and mix it in any quantity. After an outcry, Gladstone accepted the proposal of Patent Still whisky (grain whisky) which was bland and weak as the additive to Malt Whisky, in ANY proportion. But ONLY distillers could do this blending. Grocers were added in 1863, but the whiskies had to be in an inconvenient BOND house. After pressure from Scotland, this rule was withdrawn and amended and Grocers could now blend at home in Bond, providing home or the distillery in Bond was no further than one-quarter mile from town.

1786: Alexander Milne and George Taylor license Milltown distillery in 1796, making it the oldest registered plant

in Scotland.

1823: The distillery is bought by McDonald Ingram and Co.

1830: William Longmore purchases the distillery.

1880: Longmore retires and his son-in-law JG Brown takes over.

1890: The distillery is renamed Milton.

1940: J Pomeroy purchases a majority share of the distillery.

1950: Seagram purchases the distillery when Pomeroy is jailed for fraud and the

1951: The name is changed to Strathisla.

1970: The distillery begins a heavily peated run of Craigduff.

2001: Taken over by Pernod Ricard.

2013: The Strathisla brand is given a packaging update.

1820: Hires William Edwards as Manager

1828: Forrest dies. Grocery bought by William Edwards.

1828: William Edwards expands Grocery by buying 46 Castle Street. Changes shop designation to Grocer,

Wine and Spirits Purveyor and Provisions Merchant.

1834: Relocates to larger premises at 49 Castle Street. Adds Employment Agency to the portfolio.

1837: Relocates to 13 King Street.

1838: Hires James Chivas as his assistant. Chivas goes on to prove his worth.

1838: John Chivas employed by Apparel Merchant and Wholesale Dealer, DL Shirres.

1841: William Edwards dies intestate overseas. Legal formalities require closure of store.

1841: James Chivas leaves and joins food and wine merchant enterprise of Charles Stewart as junior partner,

Stewart and Chivas, 39 Woolmanhill Street. Purchase vacant 13 King Street later that year and relocate there

as a “One-stop-shop,” and excel in servicing disparate demands.

1843-51: Expand further to add 9,11 and 23 King Street. Purchase 21 King Street as residence for James Chivas.

1857: Charles Stewart leaves. John Chivas joins James as Partner, Chivas Brothers.

1862: John Chivas dies.

1886: James Chivas dies and control goes to James' son Alexander Chivas.

1893: Alexander Chivas dies, marking the end of the Chivas family’s association with products bearing their name.

1909: The first ever Chivas Regal bottling, the ultra-luxurious 25 YO makes its debut in the USA. No Chivas family member

is associated with this release, essentially dedicated to/in honour of the departed James and John Chivas.

First published on 15 Dec 2019.