NO AGE STATEMENT WHISKIES : FOOL'S GOLD?

I was anonymously sent the article reproduced infra. I don’t know who wrote this piece, nor would I care to, as this writer apparently has not studied this topic well enough to post such a blog. After numerous readings, I get the impression that the author is concerned that young No Age Statement (NAS) whiskies from prominent brands are unethically being sold at much higher prices than prime age stated whiskies from that very distillery, but does not know how to convey his apprehension. Virtually every statement made by him is either contestable or wrong.

His article is printed in BROWN. My remarks are in BLACK. I first posted this blog on 09 July and am repeating it with minor changes besides a few additions.

I too am disquieted that Master Blenders at large are bringing out NAS whiskies that are clearly younger than the whiskies they are replacing, yet carry up to a 50% price increase and will develop this global issue logically in this post.

It shows how the balance has tipped too far towards marketing at the cost of the consumer. If a distillery has only one NAS whisky, they can obviously understand that, but if it has 10 different NAS products, like Macallan and Bunnahabhain do, how does it explain the differences to the retailer, who then has to explain them to the consumer? Macallan is an LVMH brand and has its own pricing norms-take it or leave it.

On deeper analysis, one has to live with the times. Let's face it: NAS whiskies are here to stay and we might as well accept this fact gracefully.

NAS is slowly replacing many popular and excellent age stated malts. Its advance is inexorable and in time will increase as a percentage of the whiskies in the market. NAS expressions display the Master Distiller’s skills. Why are we looking at it negatively? He has, at times, to add aged malts from older casks to maintain consistency and quality. No Master Distiller would release anything but a good whisky. They are individuals whose commitment, passion and integrity will not permit them to let poor quality product releases in their name. They have too much at stake.

At the outset, please remember that the cheapest Single

Malts (entry level Single Malts like Glenfiddich 12 or The Glenlivet 12) are

far more expensive than the Luxury-level/Premium Blended Scotch brands Johnnie

Walker Black Label, Chivas Regal 12 and the like, for the

same volume. I'll explain why shortly.

WHAT IS A SCOTCH WHISKY ?

Simply put, a Scotch Whisky is alcohol distilled

from grain / grains (wheat, rye, corn or barley or a mix of 2 or more, although rye is rarely mixed) or malt (treated barley) and aged for at

least 3 years in used (wrong-new barrels may be used) Oak oak

barrels with a capacity less than 700 litres. The distillation and the complete ageing has to be in Scotland so as

that

the resultant alcohol to may be called Scotch Whisky or just Scotch. The oak barrels in

which the ageing is done have to be used before for the ageing of other alcohol

other than scotch like American Whisky (say Bourbon) or wines (say sherry)(wrong again). No additives like flavors, colors, essences whether

natural or artificial, are allowed to be added to scotch with the exception of

sugar plain caramel colouring E150A which may be added for color consistency. Scotch whiskies maybe

may be

single grain (from a single grain distillate distillery),

blended grain (by blending of different grain distillates from different grain distilleries), blended (mixing of single grain and single malt distillates), blended / pure malt (mixing of different malt distillates from different distilleries) and Single

Malts (from a single Malt Distillate distillery).

Of course there are various other types of Scotch labels

like Single Cask, but which are beyond most consumers' reach and

as well as being just variations of those mentioned above. To sum it up, all scotches

Scotch are is whiskies whisky, but all whiskies are not scotches

Scotch.

AGE OF A SCOTCH WHISKY

A whisky, to be called Scotch, has to be aged in Oak Barrels for a minimum

of 3 years. This aging gives the whisky a natural color from

the wood, flavors and properties of the wood as well as of the other alcohols

which were previously aged in them (like Bourbon or Sherry) thus giving the

whisky its character without any artificial flavoring. When the whisky sits in

the barrel for 3 or more years, a portion of it is lost due to evaporation.

This loss is termed as the ‘Angel’s share’ which indicates that the angel has

made your whisky smooth and characteristic (it has turned your whisky into

scotch) (????) so it has taken its share for the good work. The more the age of the

whisky the more characteristic it becomes and the more the loss due to the

‘Angel’s Share’ resulting in a better quality(?????????? only up to a point-check with Amrut or Paul John) albeit at a higher price as also

a higher profit for the producer. The higher price of older whiskies are also

because of significant investments in real estate, barrels and the liquid lying

within without any immediate returns. The age of the whisky can be mentioned

only if it is that many years old. Like say the whisky in a bottle of

Glenfiddich 12 year old has to be aged for a minimum 12 years and 1 day (wrong) to

mention 12 YO on the labels. For a blended whisky like say JW Black Label which

is a 12 YO, each whisky used in the blending has to be 12 years and 1 day old

or more (wrong again). Thus the years mentioned on the bottle has to be the age of the

youngest whisky in the blend and cannot be an average of the ages.

CHALLENGES TO FOR THE SCOTCH INDUSTRY

The Consumption of Scotch is increasing at a very rapid

pace but the facilities that age the Scotch into higher age, higher priced and

more profitable whiskies is not keeping pace. There is also an ever increasing

hunger to increase the bottom lines. Each producer wants to sell more Scotch

volumes without waiting for more time to age the whisky further. The Mantra is

distill more, age for the minimum period of 3 years (so that it can be called Scotch)

and sell. This way the turnaround for the whisky distilled today will be say 3

and a half years, the barrels get empty to age new whisky and less real estate

is taken up. BUT THE PROBLEM IS. . . less aged whisky simply give lesser profits,

hence lesser money for marketing, no innovation and hence difficulty in

selling (??????). THEN ONE COMPANY DECIDED TO FOOL YOU CONSUMERS (he means Johnnie Walker) by selling a less aged whisky at a price more expensive than even its own more aged whisky with a simple innovation that ‘PLAYS WITH THE MIND OF AN IGNORANT CONSUMER’. Seeing

the success of this company, all others followed suit and all of you today are fooled (NAS whiskies have been in existence since 1823, but became more relevant only in the early 1900s). Want to know how? Read on!

HOW THE CONSUMER IS FOOLED-----

|

|

Ever heard of a whisky

called ‘JW DOUBLE BLACK’ ? Comes in a beautiful blackish grey bottle, with a

label bigger than JW Black Label. The word

mentioned are ‘aged in deep charred oak casks’. The perception is that it double the quality and it is actually

JW Black Label which is further ‘aged in deep charred oak casks’. The great

quality of the bottle and the marketing hype (especially in the Duty Free)

around it projects the whisky to be double the price of JW Black Label (??????) and when you find that Double Black is

only one and a half times the price of the bottle (wrong again), you buy it with a good feeling that you

are buying the double the quality at one and a half times the price. FOOLED !

You probably did not see that the age ‘12’ is missing on the Double Black

bottle which is distinct on the Black Label bottle, Black label is a much more

aged hence better quality and more expensive whisky than Double Black (????????) but you bought Double Black at a more

expensive price. The additional profit goes into the bank account of the

producer with the remarks ‘EARNED FROM YET ANOTHER FOOL.’ An unsubstantiated statement. I will disprove it in the para infra.

The International Whisky Competition

is an event that takes place annually in a major city in the US in the 1st week of May, in

which whiskies are blind tasted and rated by a professional tasting panel. The

results are used to produce tasting notes for an International Whisky Guide.

There is no Scotsman on the panel- it is entirely American. This panel

selected Glenmorangie Signet NAS as the Whisky of the Year 2016 with 97 points and Johnnie

Walker Double Black Label was awarded the Gold Medal in the Best Blended Scotch

NAS (No Age Statement) category with 94 points, ahead of Johnnie Walker Blue Label (91.3 pts). JWBL managed only the Bronze Medal in the Best Blended Scotch Whisky 12 YO category with 89.8 points. On whiskyanalysis. com, it is rated some 80 slots lower than JWDBL, out of 1,100 top ranking whiskies. That kills the Double Black vs Black Label controversy! That also means that JWBL is no longer the bar for premium Blended Scotch Whisky.

Incidentally, the Whisky of the Year 2017 is another NAS, the Ardbeg Kelpie Committee Exclusive, with 97.3 points.

You will see many such whiskies on the shelves now, Laphroaig Triple Wood/

/ Select / Lore / Brodir, Glenlivet Nadura / Founder’s Reserve / Distiller’s Reserve / Small Batch,

The Macallan Gold / Fine Oak / Sienna, Chivas Regal Extra, Talisker Storm /

Dark Storm / Skye, JW Explorer Club- the list is endless. The producers have

more margins hence do better marketing through better packaging, hiring eye

level shelf space and paying better margins to retailers. Everyone in the chain

benefits except the poor consumer who drinks an inferior liquid at a higher

price. FOOLED! Uh Oh. He would have made his point convincingly had he selected more appropriate examples. The

JW Explorer's Club does seem overpriced. The Nadurra is a 16 YO non-chill filtered range of single malt Scotch whiskies, which have been matured in ex-bourbon casks and then bottled at cask strength with no chill-filtration. Recent editions are cask strength at 60±2% NAS. The Macallans and Glenmorangies are always over-priced; that's because they come from the LVMH stable. That branding is worth an intrinsic $20. Even so, they are actually value for money.

DON’T BE FOOLED

Get educated. Don’t look at the fancy bottle or the

label or the bigger carton box. Look at the age. Most blended scotch whiskies

start writing the age on the label when the whisky is 12 years or more (??????).

Most Single Malts do 10 year onwards (????????). Look or ask for the

age and then decide. The producer in their advertising material or through the

retailer may claim that the whisky has a unique blend achieved through pain

staking master distillation, blending or maturation in various woods, REMEMBER

about the ‘Angel’s Share’, if the angel has not taken its FAIR SHARE (more

ageing) the whisky will only be ranked FAIR. After all when it comes to Scotch

whisky, there can be no human good enough to come even close to THE ANGEL. NO COMMENT.

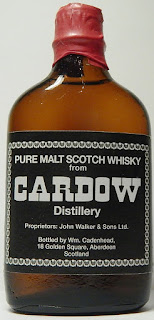

ANALYSIS OF JOHNNIE WALKER BLACK LABEL

I will digress a bit and return to the previous para later in this blog. Let’s take it one by one. In 1893, Cardhu distillery was purchased by the Walkers for £20,500 to protect the stocks of one of the Johnnie Walker blends' key malt whiskies. This move took the Cardhu silky smooth single malt out of the market and made it the exclusive preserve of the Walkers. Cardhu's output was to become the heart of Johnnie Walker's Old Highland Whisky and, subsequent to the rebranding of 1909, the prime single malt in Johnnie Walker Red and Black Labels. Sensing a promising opportunity for their brands in terms of expansion of scale and variety, they became a shareholder in Coleburn Distillery in 1915 and Clynelish Distillery Co. & Dailuaine- Talisker Co in 1916. Such a strategic expansion was made solely to ensure that the output from the Cardhu, Coleburn, Clynelish, Talisker and Dailuaine distilleries would play a major role in the definition of the extant Johnnie Walker Blends and those slated to follow.

The style of Coleburn Whisky is a bit sweet and fruity, but only independent distillers presented single malt releases. Almost all of the whisky that Coleburn Distillery had produced was used in blends, especially in the Johnny Walkers when Diageo became the owner. Virtually all Johnnie Walker blends produced today by Diageo contain Cardhu-and a lot of it; plus Clynelish, Dailuaine, Talisker, Linkwood, Mannochmore and Caol Ila. The Coleburn shut down in 1985 and its SMs were last used in Johnnie Walker Red, Black, Gold Labels and Swing in 2000. Its absence is easily found in the changed nose and palate of the JWRL and JWBL.

Today's Johnnie Walker Black

Label 12 Years Old Blended Scotch Whisky thus has Cardhu as its core malt, backed up

with the super-smooth Glenkinchie, Dalwhinnie, Blair Athol (the primary SM in Bell’s),the multi-faceted Cragganmore and Dailuaine. The recognisable Single Malts for me are Clynelish 14 YO, Cardhu, Caol Ila, Glenkinchie, Dalwhinnie, Auchroisk, Inchgower and Talisker. JW claims

that there are at least 25-28 more Single Malts and they must be right; it is a

40-whisky blend, after all. The Single Malts need not be from different

distilleries; any distillery can provide tens of Single Malts, of the same or

different ages. Cameronbridge and North British provide the single grain whiskies, from three to five.

Scottish Law says that if a distiller wishes to state a Scotch Whisky's

age, IT HAS TO BE THAT OF THE YOUNGEST WHISKY in the bottle. Therefore, all

whiskies named above are 12 YO or older. Talisker, most popular as a

10 YO, remains casked for two years more to contribute to the blend. This 12 YO

is not sold in the market, and has, sadly, not been used for over five years,

with detrimental effect on the Blend; the Taliskers in the market are the

Talisker Storm, Skye Gift Pack, Talisker Dark Storm and the Port Ruighe (all

NAS) followed by an 18 YO! I can't accept the Talisker NAS family's bumped up prices.

The

slightly smoky taste comes from the Lagavulin, Cragganmore, Mortlach & Talisker

(unpeated). The hint of peat comes primarily from Caol Ila, strengthened by the Lagavulin,

Clynelish, Glen Elgin and Benrinnes; the smoothness comes from Cardhu,

Glenkinchie, Dalwhinnie, Dailuaine, Royal Lochnagar, Blair Athol and the Grain Whiskies that

are used to tame and meld the malts perfectly. A 1-litre bottle of Black Label

costs $ 28. A bottle of 0.70 L Talisker 10 YO costs $56, or $80 per litre. The

Talisker 12 YO is far more expensive and Diageo is losing money on the Talisker

malt diverted to making the Black Label. The same is true for ALL other Single Malts that make up the once fabulous concoction of JW Black Label! The Malt

whiskies tot up to 70-72.5%. The Grain whiskies, 27-29%, are also 12 YO. The last

one half percent is taken up by E150A Caramel colourant.

Scotch

whisky can be sold with an age statement or NAS as long as it is 3 Yrs old. Every barrel is branded with the date of filling, amongst other data. Barrels

maybe opened only on the date branded, at a minimum of 3 yrs later.

It can thus be legally opened at 3 yrs + 2 days, 6 yrs + 177 days, 9 yrs + 66 days, or at exactly 12 yrs.

Grain Whisky has a rather small market as individual brands and bottlings per se; thus Grain Whisky distillers / blenders / marketers are few in number. Frankly, when it

comes to Grain Whiskies for blending with Single Malts, age is not a major criterion in taste, since a very

large percentage is stored in huge steel vats totalling in excess of 750

million litres at 95.2% strength before maturing for the three mandatory years in oak

barrels at 65% ABV. They are then decanted therefrom for use in blends. Those that mature in oak barrels

gain from it. That said, these oak barrels are generally sixth or seventh-fill

barrels, at the fag end of their lives, and have nothing on offer like colour

and flavour; most Grain Scotch is colourless, or a pale piddly colour. About 20% of the better strains in grain whisky are, however, aged like SMs. These are used for high quality blends.

Even so,

better barrels are often used as holding barrels which, after decanting the grain

whisky 3 years later, are charred and used for smoky malts.

A 6 YO Port Dundas can be as good as an

8 YO Cameronbridge and a 9 YO North British can be as good as a 12 YO Girvan. How many Grain Whisky brands have you seen at a Duty Free shop? Perhaps

Haig 15 YO; I have seen only three others, Compass Box Hedonism NAS, Loch Lomond NAS and Port Dundas 21

and I have travelled, mind you. I do not deny that there must be others, but Grain Whisky is a far cry from what you

would expect.

|

| Massive fully automated fermentation plant & washbacks at North British Grain Distillery |

|

| Caol Ila has been using wooden washbacks since 1846 |

In distilleries that grow their own barley and do their own floor malting like Kilchoman and Abhainn Dearg, it takes

anywhere between 75-100 days to convert barley into the (raw) new make that will be

casked to mature into malt whisky. The number of processes involved is amazingly

high, time consuming and fraught with inescapable losses. Most distilleries now buy maltings made to specs, including ppm. This cuts down the entire process by 40-45 days. Pot Still distillation

in the Single Malt production chain is tedious, whereas column still distillation for Grain Whisky is a rapid and high volume

process. Grain whisky takes less than a week from cooked cereal to cask and in

incredible volumes. Moreover, it provides very high consistency. A malt new

make is thus more than 5-7 times the cost of grain new make. Blends use Grain Whisky

freely, with much lower overall cost. The profit factor comes from economies of

scale and quick turnover. This is why entry level Single Malts are much more expensive than premium Blends.

JW Double Black

has an easier structure compared to Black Label, with important differences.

The number of Single Malts and Grain Whiskies has reduced. It primarily uses

the well-peated Talisker 10 YO and Caol Ila 12 YO, with the lightly peated

Cragganmore, Clynelish14 YO and Benrinnes in support. One or two Single Malts

have been replaced. Single Malt from the new distillery at Roseisle that opened

in 2006 produces 7-8 m litres a year (designed for 10 million litres), and a fair

share of young malts join the group. All Single Malts in JWDBL are 8 YO and

more, with a few drops of a couple of smoky peated Single Malts added: probably

Caol Ila 8 YO and Lagavulin 8 YO. Peated whiskies are more expensive than

non-peated expressions. The peating process between kilning, drying and mashing is tricky and time consuming.

Following the kilning, the peated malt is removed and stored in bins for five or six weeks.

This allows the heat to dissipate naturally. Hot malt can negatively affect the fermentation

process.That is why JWDBL costs more and I think that's

justified. Only FOOLS think there is tomfoolery going on.

Peated varieties

of Single Malts become expensive on the basic tenet of workload and supply

& demand. Lagavulin is really steep. The grain whiskies in JWDBL are young North British

and Cameronbridge whiskies. The Malt whiskies tot up to 75-77%, which

is why the brand costs $5-8 (12-20%) more than JW Black Label (non-discounted).

In Bangkok, they cost the same. Don't go by Delhi Duty Free prices-they are absurdly high. Since there are young whiskies in this blend in

a world where 85% of the drinking population believe old is better, the Double

Black does not state its age- nor is it required to. It is an NAS whisky, like

Johnnie Walker Blue Label NAS, JW Odyssey NAS, JW Island Green NAS, among

others. Please read these blogs on NAS whiskies and Blended Malt whiskies at:

The average buyer seems to prefer older

Scotch whiskies, and would blindly buy an older version. That is both

thoughtless and rash. For example, the Single Malt Highland Park 12 is globally rated better

than the 15, even though $17 cheaper. The blend JW Swing NAS and JW

Platinum Label 18 YO are better than the JW XR-21, though both are cheaper. The

XR-21 didn't sell, even with a 20cl Blue Label gift on purchase, as also the JW

King George V. They will reappear as different brands soon, after a little

tinkering, have no fear. In fact, the

XR-21 has already reappeared in a fresh avatar.

BLENDED SCOTCH WHISKIES

Till 1990, Scotch only meant Blended

Scotch, a mix of pot-distilled malt whiskies and column still-distilled grain

whiskies. There were three classifications: Fine, 5-7 YO; Rare, 8-11 YO and

Premium, 12 YO and more. 3 / 4 YOs were either not classified or just called 'old'. Glenfiddich and The

Glenlivet were names heard once in a while and surprise expressed that these 12

YO and older <Single Malts??> cost more than a Premium Scotch. Where did

Single Malts come from? Most Scotch whiskies were in the fine category. JW Red

Label, J&B, White Horse, Long John, Queen Anne, etc., were in the Rare

category and eminently drinkable. There were cheap 3-5 year whiskies too, like

McIvor, Wright & Greig, Duggan’s Dew, Royal Emblem, Haig Club, Will Fyffe,

Cutty Sark, Old Smuggler and the like.

Johnnie Walker Kilmarnock Special Old Highland was first sold as a 9 YO in the late 1890s/early 1900s. It was renamed Johnnie Walker Red Label and elevated to a 10 YO in 1909. It became the world’s largest selling Scotch in just a decade, right up to the early 1990s. It went NAS once JW Black Label was fully established in the 60s. You could nose it from 5 metres! The expensive but classy Black Label was reserved for celebrations. Even today, Red Label is the world's largest selling Scotch Whisky. Despite drawing progressively increasing flak for poor quality, it

retains top spot, albeit with a lesser margin, as a base whisky for mixing. It is used for cocktails or mixed with Coke. Its quality has dropped to that of a 3 YO blend, with only 30% lesser quality Single Malts of the better heads and tails categories and 69% 3 YO grain whisky straight from the casks. Johnnie Walker Kilmarnock Extra Special Old Highland 12 YO was renamed Johnnie Walker Black Label 12 YO, a multimillion seller, but the ‘Johnnie Walker’ personified is on the decline. The Age Statement on the bottle today is the age of its youngest brand. JW Black Label (JWBL) used to have the odd 18 & 21 YO brands. The 18 YO was The Singleton of Glen Ord. The 21 YO was Mortlach, which uses quadruple distillation. They are no longer available. As per current Scottish law, if an age is stated on a bottle, it must be that of the youngest Scotch Whisky in the product, [29] so mandated in the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 (SWR 2009). However, prior to this mandate, neither the Scotch Whisky Act 1988 (SWA 1988) nor the Scotch Whisky Order 1990 (SWO 1990) had enacted any laws governing age statements, besides leaving numerous other ambiguities that allowed misuse of the said SWA 1988 and SWO 1990, e.g., definitions of Single Malt, Pure Malt and Blended Grain; how Scotch Whiskies must be labelled, packaged and advertised; and where Single Malt Scotch Whisky could be bottled, etc.

As said, JW Blue Label is also an

NAS whisky, as is their most expensive $600 Odyssey Blended Malt Whisky. So,

would you advise people not to buy Blue Label or Odyssey because they do not

carry an age statement? The Blue

Label has an interesting origin. It first came out in early 1992 as John Walker's Oldest 15-60 YO

at GBP 229 and sold out quickly. It contained whiskies from Brora and Port Ellen distilleries, It was replaced as Johnnie Walker Oldest NAS, at nearly the same price later that year, again sold out quickly and was replaced in 1992 itself by the Blue Label that we see in the market today. The Blue Label was first priced at GBP 210 and has dropped to below GBP 130 today. All three versions were at 43% ABV in 750 ml bottles, with exquisite packaging. One bottle of Johnnie Walker-"Oldest" 15-60 Year Old, .75L 43% ABV Original Blue Label is available online at $1,700. The Duty Free 1.0L 40% ABV version costs between £ 130-160. The 20% of Grain whiskies in JW Blue

Label are relatively young, 15-18 years old. Some malts are 25+ years old, like the Teaninich

29 YO. Moreover, JW Black Label is no longer the bar in 12-YO Blended Scotch

whisky! Why? Because Diageo uses 40% Grain whiskies. The casks in which the

final blend is stored are of dubious provenance, as Single Malts take away all

the good bourbon and sherry casks.

As said, JW Blue Label is also an

NAS whisky, as is their most expensive $600 Odyssey Blended Malt Whisky. So,

would you advise people not to buy Blue Label or Odyssey because they do not

carry an age statement? The Blue

Label has an interesting origin. It first came out in early 1992 as John Walker's Oldest 15-60 YO

at GBP 229 and sold out quickly. It contained whiskies from Brora and Port Ellen distilleries, It was replaced as Johnnie Walker Oldest NAS, at nearly the same price later that year, again sold out quickly and was replaced in 1992 itself by the Blue Label that we see in the market today. The Blue Label was first priced at GBP 210 and has dropped to below GBP 130 today. All three versions were at 43% ABV in 750 ml bottles, with exquisite packaging. One bottle of Johnnie Walker-"Oldest" 15-60 Year Old, .75L 43% ABV Original Blue Label is available online at $1,700. The Duty Free 1.0L 40% ABV version costs between £ 130-160. The 20% of Grain whiskies in JW Blue

Label are relatively young, 15-18 years old. Some malts are 25+ years old, like the Teaninich

29 YO. Moreover, JW Black Label is no longer the bar in 12-YO Blended Scotch

whisky! Why? Because Diageo uses 40% Grain whiskies. The casks in which the

final blend is stored are of dubious provenance, as Single Malts take away all

the good bourbon and sherry casks.

The Blended Scotch market, which has

the cheapest Scotch whiskies, has reduced by 10% in the last 5 years. Lots of

names have fallen by the wayside, like Haig, McCallum's, Sanderson's GOLD, JW Red Label, Scottish

Glory, etc., all now meant for mixing cocktails.

NO AGE STATEMENT WHISKIES

NAS came about with the advent of

Single Malts starting 1978-81. The Single Malts fetched a much much better

price on their own; using them in blends was not cost-effective, hence alternatives

were required to retain consistency. Look at it from the Blender's viewpoint:

In 1997, he used his JWBL recipe to produce that classic Black Label. This

blend was of Single Malts aged 12 years or more, i.e., casked in 1985 and

earlier. In 1998, he pulled out his recipe and tried it out with Single Malts

casked in 1986 or earlier. He could not use some of the defining Single Malts

of 1985, because THEY WERE ONE YEAR OLDER and tasted different. So, a search

was launched to replace five or six branded malts that were not balancing out.

In a short while, he achieved success! Now, let’s move a decade up.

Till 2007, JWBL is available in the

market in its original avatar. But in 2008, the imbalance is larger and

REPLACEMENTS are not found in stock. Royal Lochnagar produces only 450,000

litres of Single Malt per year, mostly diverted to the JW Blue Label NAS. Ergo,

the Black Label has a slightly different taste. Their Master Blender

(Jim Beveridge) is in a tight spot -the inconsistency is too much for the

market. He does not have stocks of Single Malts. Talisker, the main peated

ingredient in a $36 (original price) Black Label sells at $56-62 on its own for a 0.7 L bottle.

So do Clynelish, Teaninich, Benrinnes, Dailuaine and Linkwood, important parts of

JWBL. Caol Ila produces 6.5 million litres of Single Malt whisky a year, but

20% is sold as Caol Ila Single Malts (5,8,10,12,16,18,21 and 30 YOs). Right up to 2005, this was just 5%. The unpeated

version is in short supply. Earlier, it was freely available for blending.

Common sense says: Sell Caol Ila, Talisker, Dailuaine and Linkwood as Single

Malts, by themselves. So, Black Label drops off the pole position; by 2013, the Black

Label goes for volumes and discounts. The price is reduced to $28! It is

permanently on sale somewhere or the other. Diageo is now working on economies

of scale, dropping prices to entice the public to keep buying this iconic

whisky. Ab initio drinkers are excluded, anyhow.

During his experiments to get the balance right, he discovers that one blend can be given a pronounced smoky and

peaty taste. Talisker 10 and Caol Ila 12 join up with Cardhu as the core SMs, and the blend's smoky and

peaty taste can be accentuated by using charred casks. He isolates these additions and finds that they are pominent 8YOs on their own right, like

Caol Ila 8 and Lagavulin 8. A quick look at the stock position shows that he can add these SMs freely and run them

for one year. If the market response is good, he will supplement JWBL with this darker, smoky and peaty expression.

He tests it in 2010 and it is good, so much so that Diageo directors agree to giving this brand a label of its own.

Since it is a derivative of JWBL, JWDBL is found to be the best suggestion and is approved, but as an NAS edition, since

it uses 8 YOs, and in an era where 'Old is Gold' is the diehard tagline, a JWDBL 8 YO will instantly excite disapprobation even before tasting.After a hugely successful launch in travel retail as a 1L bottle in 2010, it was rolled out for general release in 2011 as a 70Cl 40% ABV brand.

The preponderance of No Age Statement whiskies has stoked a furore among some aficionados, which may no longer be sustainable. As a result of the unforeseen increased demand for old age single malt whisky stocks, the whisky baories are running a little dry. The lack of transparency has infuriated a few. Do note that such an outcome was recognised decades ago by prescient producers such as Ardbeg and Glenmorangie, where Dr Bill Lumsden is the Master Blender.

“We’ve successfully been releasing NAS whiskies for 20 years with Glenmorangie and Ardbeg and they are doing very well,” says Lumsden who has blended a plethora of successful NAS whiskies for both LVMH brands. His theory is simple: if you have the makings of a good whisky, all you need is a good barrel. The Ardbeg Kelpie, Corryvreckan, Uigeadail, Ardbog, Galileo, Supernova, Perpetuum, etc., and the Glenmorangie Signet, Bacalta, The Tarlogan, Tayne, Dornoch, The Duthac and many more have kept their tills ringing while accumulating awards galore, proving his posit.

For Glenmorangie, he makes copious use of the Devil's Cut, aka ‘indrink’, the liquid absorbed into the wood during maturation mainly in the Sherry industry. About 12% of maturing Sherry/Wines are absorbed into the barrel. Sherry needs 2 yrs maturation in 500L barrels, so 60L of Sherry awaits the new make/Scotch whisky if a barrel switch is made for secondary maturation, or a Sherry barrel used for the primary. He adds a note of caution, “Regardless of what you are doing, young whisky in bad wood will be ruthlessly exposed.”

The Chivas Regal Effect: One interesting note from popeconomics/marketing culture is the ‘Chivas Regal Effect,’ which occurs when a product sells more because the price of it has been increased. Since people often equate price with quality, consumers, who otherwise would not have purchased a product, might choose it because it is more expensive (and thus ‘better’ quality). Wine(a 1982 St. Emilion) is a good example of this effect in the world of alcohol and LVMH in branded consumer luxury goods. NAS whisky distillers are canny enough to implement this concept, which have left many consumers in an ambivalent frame of mind.

There are many reasons to justify the NAS, but in some cases the whisky hasn’t met with expectations in terms of quality. Taking younger single malts and blending with older is not a problem, since distilling and wood management techniques have greatly improved in recent years, but the whisky still needs to be satiating. “People should make a judgement on quality alone and not be swayed by the importance of age,” says Euan Mitchell, MD at Arran Distillers.

Even so, I am not prepared to accept Mitchell's "summing it all up" statement. There are far too many brands

out there, veritably slugging it out in a tight market, a major portion of which is reserved for the VIP Brands.

There is bound to be the less scrupulous distiller or private bottler who will cut corners. Such products that don't

meet quality standards dictated by their price must be brought to book. But how? Who will dictate or define standards, as one man's uisge could be another man's hooch?

I

foresee and forecast that there is no future for Blended Scotch except truly

rare brands. Only 3-400 of the 3,000+ brands will remain. Half will be

exorbitant, priced like the Macallan and LVMH SM brands and the other half will remain for

the proletariat, like Teachers, Grants, Bells, Famous Grouse, Lawson, Highland Queen,

etc. As of 2010, 91% of all Scotch sold was Blended. That figure has dropped to 83% in 2015 and by

2030, will further drop to 50%, declining till doomsday. The world has

discovered Single Malts and people will have enough money to buy them. Both

Johnnie Walker and Chivas Regal have moved into NAS and these brands will

sustain them. Johnnie Walker will survive on its Black Label, Green Label,

Island Green Label NAS and Blue Label NAS, apart from usurious special

editions. Chivas is promoting its NAS Blended Malts, the Ultis, Extra and Mizunara and its iconic 21-YO

Royal Salute will last the distance.

Remember that Diageo is a market

entity, with no room for sentiment where cash flow is concerned. They closed

down the Kilmarnock facility in 2012 against strong local and government

demand, despite its history as the home of Johnnie Walker who sold his first

Walker's Kilmarnock Whisky there in 1820 and of succeeding generations.

Let’s get back to that erudite para:

DON’T BE FOOLED CONT'D

Get educated. Don’t look at the fancy bottle or the label or the bigger

carton box. Look at the age. Nearly 60% of all

Scotch available is NAS. That includes the JW Blue Label and the $600 Odyssey.

Again, will you stop buying Blue Label because it is an NAS whisky?

Most blended scotch whiskies start writing the age on the label when whisky

is 12 years or more. (!!!*!!!)

Single Malts, and by extension, Blends (mostly NAS) are available in the

3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 13,14,15, 16, 17,18,19,20,21,23, 25, 29 & 29+

range. Bowmore's bestseller is a 9 YO SM. Amrut & Paul John sell 3-7 YOs

only. ABVs > 65% over a couple of years eat into the wood beyond the red layer and become ROTGUT.

There are a host of 3 YO Blends in the market, with age statements, like Scottish Leader, Smokin' - The Gentleman’s Dram, Scottish Glory, Statesman,

Taste, ASDA, Tesco's Special Reserve, MacQueens, Scots Club and Waitrose, among

others.

The Carlton, PM and Glen Rowan are nifty 4 YOs.

Some good 5 YO Blends are on offer, like Mackinlay, Bank Note, Cluny, Glen Orrin, Golden King, Red Hackle, Loch Ness and Lismore, etc.

The Age Statement on the bottle

represents the age of its youngest brand.

8 YO Blends available freely are Bell's Christmas Series, starting 1955;

Fortnum & Mason; Black Dog Reserve; Buchanan, starting 1980; Inver House;

Gilbey's Special Export; Dewar's White Label and more.

Most Single Malts do 10 year onwards. (!!!!**!!!!) There are over 1,000 Single Malt brands selling

3/4/5/6/7/8/9/ up to 31 YO+. Highland Park, Bunnahabhain, Glenrothes, Tamdhu,

Glendronach, Benrinnes, Glen Moray, Port Askaig, Tomatin, Craigellachie,

Lagavulin, Mortlach, Ledaig, Dufftown, Blair Athol, Glenturret, Deanston,

Kilchoman, Bruichladdich, Amrut, Paul John, Kavalan. . . 100s more. But I don't quite like the prices of Bunnahabhain and Bruichladdich SMs.

3 YO Single Malts include Kilchoman

2011 Port Cask Matured (bottled 2014), Glenglassaugh 3 YO 2009 - The

Chosen Few, Kilchoman Inaugural 100% Islay, Bruichladdich's Perilous X4 Spirit,

Arran 2005 Bourbon Cask Peated, Abhainn Dearg and many more. There are 4,5,6,7

YO Single Malts as well, including the 5 YO Bruichladdich Octomore Peat

Monsters 06.1., 7.1 & 7.4

In Blends, the 10 YOs include Master of

Malt 10 Year Old Blended Whisky, Johnnie Walker Select Cask, Old St Andrews

Twilight, Bell's 10 YO, Moidart 10 Year Old, Black Bottle, The Tweeddale Blend,

Famous Grouse, Imperial, Dalvegen, The Feathery,

Excalibur Excellence, Excalibur Gold and more. There are 3,4,5,6,7 YO Blends as

well. . . the list is endless.

Back to the article> “Look

or ask for the age and then decide. The producer in their advertising material

or through the retailer may claim that the whisky has a unique blend achieved

through pain staking master distillation, blending or maturation in various

woods, REMEMBER about

the ‘Angel’s Share’, if the angel has not taken its FAIR SHARE (more ageing)

the whisky will only be ranked FAIR.” (UH OH!). The ‘Angel’s Share’ is the amount of new make

that evaporates every year from the barrel, about 1.8-2.2%. The heart of the new make which arrives at 70+% ABV is cut at usually 68-50% ABV and routed

via the Spirit Safe-where the Customs/ Bonds House man sits- to the casking

chamber, where it is

poured into barrels for maturing. Alcohol in a barrel for maturing can ONLY be called new make.

The Angel's share has been

misrepresented. The more the new make lost to the angel (evaporated), the less

the contained qty of new make & the greater the wood to new make

interaction. The new make can be called Scotch Whisky ONLY after extraction

from the barrel.

A Scotch Whisky can be finished in

another oaken barrel, ex bourbon/wine/sherry/ rum/ brandy/cognac/port, etc.

A high-alcohol concentration, say 70%,

extracts more of the beneficial compounds and colour from the wood. It also

extracts more tannins and wood-related impurities, which makes the flavour

harsh. Furthermore, higher alcohol content requires more water to dilute it to

bottling strength post-ageing. It has been found that for ageing whisky in new

barrels, 58% to 65% ABV is the ideal strength, 63.5% is the standard filling

strength, to balance barrel extraction and colour with lower tannins. It also

lessens dilution of “barrel compounds”, the organoleptic compounds extracted

from the barrel wood, at bottling time.

Lower alcohol concentration results in

slower ageing as the rate of chemical change and wood extraction is reduced.

Barrels used more than once can age stronger spirits since available tannins

have been reduced to lower levels by its previous contents. At 55% to 65% ABV,

barrels tend to have a greater porosity for water, thereby retaining fusel

alcohols, acids, esters, aldehydes, and furfural. These lower strengths result

in an increase in alcohol content after ageing, whereas alcohol strength

decreases when spirits are aged at higher alcohol concentrations.

Apparently the author shares my concern, and thus has a point, but does not know how to put his point across, unnecessarily making himself appear a tyro. His examples are wrongly chosen. His style of writing is suspect and he often jumps the gun, shooting himself in the foot. If he has his way, prominent NAS Scotch Whiskies would go off the shelves. You’d lose JW Blue Lanel, JW Odyssey Blended Malt, JWRL, JWDBL, many Laphroaigs, Ardbegs, Arrans, Glenmorangies, Macallans, Chivas Regal Ultis & Extra, Bruichladdichs, Kilchomans, Taliskers, Aberlour A’bunadh, Hibiki Harmony, Yoichi, Miyagikyo, Amrut, Kavalan, the Glenfiddich Cask Collection, The Glenlivet Alpha, etc. Early day whiskies, in fact most of the fine and rare whiskies of the 1950s and 60s were and still are NAS, like Vat 69, Cutty Sark, Black and White, Dewar’s, White Horse, Hankey Bannister, Ballantine’s, The Famous Grouse, J&B, Haig, Queen Anne, Lord Elcho, etc.

I'm afraid I cannot agree. As long as people like what they are drinking, regardless of age, NAS whiskies are here to stay.

Old age-stated whiskies will be reserved for connoisseurs and, of course, the epicures.

“After all when it comes to Scotch whisky, there can be no human good

enough to come even close to THE ANGEL.” Disregard this pious but irrelevant statement.

This blog has been replicated on https://noelsramblings.blogspot.in/2017/10/nas-whiskies-fools-gold.html

which will be taken down soon.

A lot of people write about whisky, and if you have to

believe them, there are only excellent whiskies. That is simply not true. There

are a lot of excellent whiskies, yes, as there should be, because good whisky

today is expensive! But there is a lot of indifferent product and some stuff is

just not good enough. There is a clear need for independent reviewers. I am one

of them. I have nothing to do with the industry. I don't sell anything. I don't

have the perfect Palate. My opinion is as good as yours! I just taste whiskies

and tell you what I think about them. That's all. And I don't peddle horseshit

on my blogs.

I do not collect any data on my blogs in the form of cookies, trackers, etc.Google might be using its adsense cookies.

As said, JW Blue Label is also an

NAS whisky, as is their most expensive $600 Odyssey Blended Malt Whisky. So,

would you advise people not to buy Blue Label or Odyssey because they do not

carry an age statement? The Blue

Label has an interesting origin. It first came out in early 1992 as John Walker's Oldest 15-60 YO

at GBP 229 and sold out quickly. It contained whiskies from Brora and Port Ellen distilleries, It was replaced as Johnnie Walker Oldest NAS, at nearly the same price later that year, again sold out quickly and was replaced in 1992 itself by the Blue Label that we see in the market today. The Blue Label was first priced at GBP 210 and has dropped to below GBP 130 today. All three versions were at 43% ABV in 750 ml bottles, with exquisite packaging. One bottle of Johnnie Walker-"Oldest" 15-60 Year Old, .75L 43% ABV Original Blue Label is available online at $1,700. The Duty Free 1.0L 40% ABV version costs between £ 130-160. The 20% of Grain whiskies in JW Blue

Label are relatively young, 15-18 years old. Some malts are 25+ years old, like the Teaninich

29 YO. Moreover, JW Black Label is no longer the bar in 12-YO Blended Scotch

whisky! Why? Because Diageo uses 40% Grain whiskies. The casks in which the

final blend is stored are of dubious provenance, as Single Malts take away all

the good bourbon and sherry casks.

As said, JW Blue Label is also an

NAS whisky, as is their most expensive $600 Odyssey Blended Malt Whisky. So,

would you advise people not to buy Blue Label or Odyssey because they do not

carry an age statement? The Blue

Label has an interesting origin. It first came out in early 1992 as John Walker's Oldest 15-60 YO

at GBP 229 and sold out quickly. It contained whiskies from Brora and Port Ellen distilleries, It was replaced as Johnnie Walker Oldest NAS, at nearly the same price later that year, again sold out quickly and was replaced in 1992 itself by the Blue Label that we see in the market today. The Blue Label was first priced at GBP 210 and has dropped to below GBP 130 today. All three versions were at 43% ABV in 750 ml bottles, with exquisite packaging. One bottle of Johnnie Walker-"Oldest" 15-60 Year Old, .75L 43% ABV Original Blue Label is available online at $1,700. The Duty Free 1.0L 40% ABV version costs between £ 130-160. The 20% of Grain whiskies in JW Blue

Label are relatively young, 15-18 years old. Some malts are 25+ years old, like the Teaninich

29 YO. Moreover, JW Black Label is no longer the bar in 12-YO Blended Scotch

whisky! Why? Because Diageo uses 40% Grain whiskies. The casks in which the

final blend is stored are of dubious provenance, as Single Malts take away all

the good bourbon and sherry casks.