HOW STANDARDS EVOLVED IN BOTTLING

WHISKY BOTTLES

Ancient civilizations kept their favourite fermented drinks safe in containers made of natural materials like clay, wood, and animal skins. The ancient Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans made elegant containers called amphorae. An amphora was a ceramic jar with a long neck and two vertical handles for portability. Glass was also available, but extremely expensive and used mainly to create decorative pieces. Skilled glassblowers did create beautiful bottles with intricate shapes and details, functional works of art to be proudly displayed on the tables of kings and nobles, down to miniatures for perfumes, massage oils, skin lotions, etc. By the mid-17th century, they were still expensive, but the wealthy class had increased and more people could now afford them. They were mainly used as ‘serving bottles’ or decanters, rather than ‘binning bottles’ for storing wine in the cellar.

Glass pads, impressed with the owner’s mark or coat of arms, were attached to each bottle, and the bottles themselves were taken to be filled by the wine merchant, or filled in their owners’ cellar by the butler (i.e. ‘bottler’). Within only a decade or so, the middle classes were also able to afford glass bottles: Samuel Pepys records in his diary of 1663 that he ‘went to the Mitre’ to see wine put into his ‘crested bottles’.

The earliest glass bottles had spherical bodies and long, parallel necks, with a rim at the top to hold down the string which kept the stopper in place. They are known as ‘shaft and globe bottles’. By 1700 the neck had begun to taper and the body to become compressed - these are ‘onion bottles’. They continued to be treasured, and in Scotland were commonly used as decanters for whisky in public houses. In the Highlands, it was traditional to give them as marriage gifts, crudely engraved with the names of the bride and groom, the date of the nuptials and even with an illustration of the event.

In 1643, the British Parliament introduced an excise duty on aqua vitae, in order to finance Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army. Between 1707 and 1823, tax on ‘spirituous liquors’ was increased on 17 occasions. Between 1786 and 1803, a span of 17 years, the duties on stills had increased by a factor of more than 77 times. To compound matters, a heavy tax on glass was introduced in 1746. The taxes meant that whisky distillers and drinkers started to look for alternative and discreet ways to store their whisky. Stone and ceramic pots and bottles became widely used as they provided a vessel that was both cheap and durable. Ceramic pots were also discreet, especially important if a distillery wanted to avoid paying their taxes. The durability of ceramic and stone became an increasingly important consideration as sea trade began to boom in the 18th century.

Between 1700 and 1720,

the onion shape was sometimes exaggerated, so the body became wider than the

height, then about 1720 the sides began to be flattened by rolling on a steel

plate while the glass was cooling - a process called ‘marvering’ – in order to rack them in the ‘bins’ of the cellar.

Early marvered bottles were ‘mallet’ shaped, where the straight sides tapered away from the base, but over the next twenty years, they became taller and more cylindrical,

particularly after 1740, by which time the value of maturing wine in the bottle

was becoming generally recognised. By the mid-century, many wine and spirits

merchants had their own bottles, with their name or trademark pressed into the

glass pad, to be returned for refilling with whatever liquor was available.

It was the same story for most of the 19th century across the pond. Small oak barrels were the major package for selling bourbon to consumers. The distillers would sell the barrel either to a saloon or spirits shop, and that business would sell to the consumer. Very few retail establishments bottled the bourbon due cost of glass. Instead, they depended upon the consumer to bring their own flask or jug.

Honesty was at stake at some sellers, far more so in America which didn’t really care for core values in the land where a gun was the law. The problem was that the consumer only received what the spirits shop owner provided, whether sold out of the barrel and in the bottle. They would often water down the spirit or add fruit juice and brown sugar to darken the product and give it a sweeter taste. Even with the most honest retailers in the UK, the whisky would change in the anker, later the sherry or port barrel, as it was emptied and the spirit oxidised. Since customers never really knew what they were getting out of those barrels, consistency of the whisky became a problem.

The classic French wine

bottle shapes familiar to us today had evolved by about 1800 – there was a huge

growth in the number of glass factories in Bordeaux, particularly, which was

producing around two million bottles a year by 1790. Bottles from this period

can often be identified by a slight swelling around the base, caused by the

glass ‘sagging’ while the bottle cooled in an upright position.

Until 1821 bottles were

free-blown, which meant that capacities and dimensions were not standardised.

So when one reads of hearty drinkers of the late 18th century

downing three or four or even six bottles of wine at a sitting – this seems to

have been especially common among Scottish judges of the period, who habitually

drank claret while sitting in judgement – it might be supposed that the bottles

of their time were smaller than those of today. Not so. Research done in the

Ashmolean Museum in Cambridge shows that the average bottle size was if

anything slightly larger than today.

In 1821 Henry Ricketts, a glass manufacturer in Bristol, patented a method of blowing bottles into three-piece moulds, which made it possible to standardise capacity and dimensions. Such moulds left seam marks – the way in which collectors identify them today – but during the 1850s a process was developed to remove these by lining the

mould with beeswax and sawdust, and turning the bottle as it was cooling.

Until about 1850 all wine

and spirits bottles were made from ‘black’ glass – in fact, it was very dark

green or dark brown – owing to particles of iron in the sand used in their

manufacture. Clear glass bottles and decanters were made, but they were taxed

at eleven times the rate of black glass.

Indeed, owing to the

Glass Tax, bottles remained expensive and continued to be hoarded and re-used

until after 1845, when the duty on glass was abolished. The earliest known ‘whisky

bottles’, such as a Macallan bottled by the local grocer in Craigellachie in

1841 (and reproduced in facsimile in 2003), were reused wine bottles. Even

after the duty had been lifted and clear glass began to be used more, whisky

makers continued to favour green glass bottles, often with glass seals on their

shoulders. VAT 69 continues this style of bottle.

The Bottled-in-Bond(BIB) act of 1853 created a whole new market for bottled whisky by separating malt whisky from blended whisky in the marketplace. Each BIB’s tax stamp seal was a guarantee against tampering. The tax stamp also gave the consumer valuable information as to where and when the whisky was made and bottled. As a result, drinkers gained confidence in the quality of the whisky in the bottle, and they began to prefer bonded whisky to whisky sold from the barrel.

Many whisky companies continued to fill into small casks and stoneware jars and offered their goods in bulk. It was not until 1887 that Josiah Arnall and Howard Ashley patented the first mechanical bottle-blowing machine, allowing bottled whisky to really take off. In the trade bottled whisky was termed ‘cased goods’, since it was sold by the twelve-bottle lot packed into stout wooden cases, like top-quality wine today.

This time, events in America preceded practices in the UK. The fact that bottles were expensive in the 1870s makes what George Garvin Brown—later to become famous as Brown & Forman— did more remarkable. In 1870, Brown was spending his formative younger days as a pharmaceutical salesman and receiving complaints about the quality of the whisky his employer was selling changing over time. Brown may have been inspired by Hiram Walker who was selling Canadian Club in the bottle as well as the barrel at that time.

He crafted the idea of a bottled bourbon where the quality would not change. The fact that Walker’s Canadian Club was selling well by the bottle even at the additional expense proved that it could be done. He entered the whiskey business and Old Forrester (as it was originally spelled) was born; today’s Brown and Forman took root then. Old Forrester was sold only by the bottle to ensure the quality of the brand. Note that it wasn’t the first bottled bourbon, rather it was the first bourbon sold only by the bottle.

Bottled whisky, properly

stoppered and sealed, was less liable to adulteration or dilution

by unscrupulous publicans and spirits merchants than whisky sold in bulk, and

during the 1890s cased goods became the commonest way for whisky to be sold,

particularly in the off-trade.The invention of the automatic glass bottle-blowing machine in 1903 by Michael Owens industrialised the process of making bottles, making it much more efficient.

The use of plastic

(polyethene) bottles, developed during the 1960s and adopted by soft drinks manufacturers, has largely been eschewed by the whisky industry, except for miniatures supplied to airlines. These bottles are called PETs – not a reference to their diminutive size, but to the material they are made from:

Polyethylene Terephthalate. Their clear advantage is weight, and they began to

become commonplace in the 1990s. Concerns about shelf-life and contamination

by oxygen or carbon dioxide have been addressed since 1999 by coating the outside

of the bottle with an epoxy-amine-based inhibiting barrier.

BOTTLE CAPACITIES

As mentioned in relation to William Younger’s examination of bottles from between 1660 – 1817 in the Ashmolean Museum, the capacity of wine (and therefore whisky) bottles remained relatively constant at around 30 Fl.Oz (1 1/2 pints) during this period, in spite of bottles being free-blown.

With the introduction of moulded bottles in the 1820s it became much easier to standardise capacity, and

this was fixed at 26 2/3 Fl.Oz (or one-sixth of a gallon, which is also

equal to four-fifths of a U.S.

quart).

In 19xx this capacity was

defined by law for a standard bottle - along with 40 Fl.Oz (equal to an Imperial quart – 2 pints), 13 1/3 Fl.Oz (half bottle), 6 2/3 Fl.Oz (quarter bottle), 3 4/5 Fl. Oz (miniature)

– and in 19yy it was required that the capacity be stated on the label, along

with the strength of the whisky.

American capacities are slightly different. 1 U.S. liquid pint = .832 Imperial pint (12 Fl.Oz.). Whisky

was commonly sold by the Imperial quart (40 Fl.Oz) or by the ‘reputed quart’,

4/5th U.S. quart or 26 2/3

Fl.Oz.

From January 1980

capacities have been expressed metrically on bottle labels, in line with the

Système International d’Unités, when 26 2/3 Fl.Oz became 75 cl, half

bottles 37.5cl, quarter bottles 18.75cl

and miniatures 5cl.

In 1992 the standard

bottle size throughout the European Community was lowered to 70cl.

The United States retains

fluid ounces, with the ‘reputed quart’ remaining the standard bottle size

(75cl).

In Japan, both 75cl and

70cl bottles are acceptable.

BOTTLE NUMBERS January 1884 – December 1909

During this period, some

bottle-makers embossed a number in the base of their bottles. This is useful

for dating bottles during the ‘Whisky Boom’. This list came from www.antiquebottles-glassworks.co.uk, an

invaluable site for bottle collectors.

1884: ****1 – 19753 1891: 163767 – 1901: 368154 –

1885: 19754 – 1892: 185713 – 1902: 385088 –

1886: 40480 – 1893: 205240 – 1903: 402913 –

1887: 64520 – 1894: 224720 – 1904: 425017 –

1888: 90483 – 1895: 246975 – 1905: 447548 –

1889: 116648 – 1896: 268392 – 1906: 471486 –

1890: 141273 – 1897: 291240 – 1907: 493487 –

1898: 311658 – 1908: 518415 –

1899: 331707 – 1909: 534963 –

1900: 351202 –

WHAT COLLECTORS ESTEEM

|

Age |

Free-blown and moulded (pre-1870) bottles have ‘pontil marks’ on their bases, created by an iron rod, called a pontil, used to manipulate the molten glass. |

|

Rarity |

The fewer known examples, the more valuable the bottle will be. |

|

Texture |

Variations in glass surface, number of bubbles in the glass, stretch marks, or changes in colour. |

|

Colour |

Unusual, dark or strong colours, or a colour which is rare for that kind of bottle. |

|

Embossed |

Where bottles are embossed (uncommon in early whisky bottles), clarity of the embossing, its heaviness (heavier the better), its intricacy and the interest of the design or words. |

|

Shape |

The aesthetic quality of some bottles. |

|

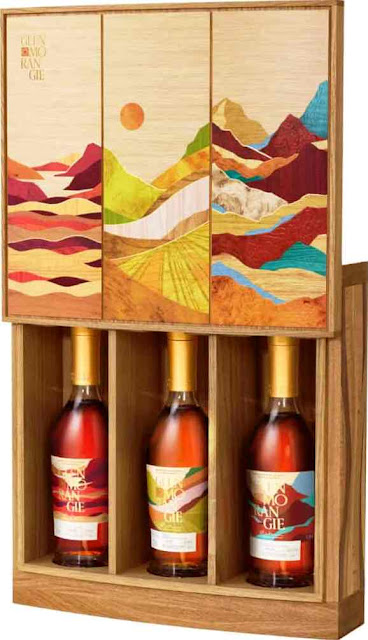

Labels |

Any item with its original label, contents, carton or box is of more interest than an ‘empty’. |

AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

Aqua Vitae was first distilled as a medicinal

tonic, but its pleasant attendant corollaries were addictive, and by the end of the 17th century its popularity began to boom across

the UK. Glass is inert and impermeable and so it was the perfect solution when

the first distillers were looking for a way to effectively preserve and

distribute their spirit to its ever-growing audience.

Glass whisky bottles were made by specialised glass blowers and were expensive to produce. A hand-blown bottle

was typically between 600-800ml (60-80cl) because that was the average lung

capacity of the glass blowers of the time. Due to the expense and luxury of the

glass, the whisky connoisseurs of the 17th century would have taken their own

bottles to be filled.

CERAMIC POTS: 1707-1850

Incessant taxation put serious strains on

the whisky industry with many distilleries shutting down and some choosing to

go underground and produced whisky illegally. A heavy tax on glass was also introduced in 1746. The taxes meant that whisky

distillers and drinkers started to look for alternative and discreet ways to

store their whisky.

Stone and ceramic pots and bottles became

widely used as they provided a vessel that was both cheap and durable. Ceramic

pots were also discreet, especially important if a distillery wanted to avoid

paying their taxes.

The durability of ceramic and stone became an increasingly important consideration as sea trade began to boom in the 18th century.

The taxes and booming sea trade are also

linked to the dawning rise in popularity of miniatures. Miniatures provided a

practical solution for sailors as they were cheaper than full bottles but the

other cheap alternatives – beer and wine, which had been favourites at the time

– did not fare well at sea. Miniature

spirits mixed with sours became sailors’ tipple of choice.

In the early 1900s, bottle sizes became

standardised in UK law

A MINIATURE BOOM: 1850-1970

At the turn of the 20th century, as taxes on alcohol continued to soar and two World Wars took their toll, miniatures

became increasingly popular on land due to their affordability. Throughout the

first and second World Wars buying a standard size bottle was considered

frivolous spending. A miniature on the other hand provided a more economical

option, allowing an occasional indulgence without having to splash out on a

whole bottle.

STANDARDISING BOTTLE SIZE

When was bottle size first standardised in

the UK?

In the early 1900s, bottle sizes became

standardised in UK law. The standard was set as 26 2/3 fluid ounces, which was

simply the average size of the traditional bottles produced by glass blowers in

the 17th century.

This standard was used until the start of

1980 when metric volume was introduced.

The standard size for Scotch whisky bottles

changed to 70cl in 1990

When was metric bottle size introduced for

whisky bottles?

On the 1st January 1980 the global standard for wine, spirit and liqueur bottles came into force converting liquid ounces

to metric volume. Standard whisky bottle size was set at 750 ml, also commonly

denoted as 75cl. This is the standard still used in much of the world today,

including the USA.

What is the standard bottle size for Scotch

whisky?

On the 1st of January 1990, the European Union updated their standard bottle size for spirits to 70cl or 700ml. This was

because a 700ml bottle is an ideal volume for pubs, clubs, and bars, which

have the option of selling 25ml or 35ml measures.

Since the 1st of January 1990, the standard

bottle size used by the Scotch whisky industry has been 70cl.

Can I use standard bottle sizes to date my

whisky bottle?

The set dates mentioned above mean that for Scotch whisky, bottle size can be used as an indicator of the bottling era.

That being said, care must still be taken as bottles designed for export for

example to the USA are still 75cl, and so other factors must be considered

also.

As well as a variation in the size of

miniature bottles, half bottles – whether 13 1/3 Fl oz, 37.5cl or 35cl – have

been popular throughout the last century of whisky drinking. Even quarter

bottles can occasionally be found for curious collectors so bottle size should

always be used with other indicators for accurate dating.

THE 21st CENTURY: AN UNSTANDARDISED STANDARD

While the official bottle size for whisky

and other spirits is set across most of the world and has been set for many

years, as mentioned above, you still will find a large variation in bottle

sizes. And one that is only increasing.

As whisky increases in value bottlers look

at different ways to appeal to and provide value for their drinkers. Many

Japanese whiskies for example are bottled at 50cl and this trend for

smaller-than-standard bottle sizes is one that is expanding in the modern

single malt Scotch whisky market too.

Smaller bottles, such as 50cl offerings,

are becoming increasingly common. Similar to the appeal of miniatures at the

start of the last century, 50cl bottles offer a more accessible way to indulge

in your favourite tipple. As well as reducing the volume and therefore cost of

the whisky, smaller bottle sizes reduce the VAT and duty due on the bottle,

again offering a more attractive proposition for drinkers – and a more

accessible entry point to appeal to new drinkers – while allowing bottlers to

maintain their own margins on more expensive casks.

Whatever your feelings on whisky bottle

sizes and the reasons behind why they change, the history of the whisky bottle

has shown us that preferences change regularly and for a myriad of reasons.

These days you can even get whisky in a

pouch, so who knows what will be next.

Why a Pint is Bigger in the UK Than in the US

An American will find a pint of beer in London looking similar to his customary pint back home, but, given the amount of the golden-brown, oddly warm liquid sloshing around in the glass vessel, it will seem to be much larger!

How Big Is a Pint?

This is because a pint in the United Kingdom is bigger than a pint in the United States. The UK pint is 20 fluid ounces, while the US pint fills up 16 fl oz. However, this translation is not that simple, as fluid ounces do not equal one another across the Atlantic. Here is the breakdown of volume between the two countries:

- The British Imperial fluid ounce is equal to 28.413 millilitres, while the US Customary fluid ounce is 29.573 ml.

- The British Imperial pint is 568.261 ml (20 fluid ounces), while the US Customary pint is 473.176 ml (16 fl oz).

- The British Imperial quart is 1.13 litres (40 fl oz), while the US Customary quart is 0.94 L (32 fl oz).

- The British Imperial gallon is 4.54 L (160 fl oz), while the US Customary gallon is 3.78 L (128 fl oz).

BACKGROUND OF ENGLISH UNITS

At the root of this divide is the

difference in measurement systems. While the American system of measurement

often is referred to as the Imperial System, this usage is erroneous. The US,

ever since the formative years of the New World nation, has used the US

Customary System. The Imperial System, alternatively, was established in 1824

for Great Britain and its colonies. Even today, decades after officially

switching to SI (metric) units, volume in the UK is measured in British

Imperial units. Both these systems, however, are derived from English units.

English units were in use until the early 1800s, and they saw a vast range of

influences due to the frenzied history of the British Isles. This historical

precedence spanned a millennium, so, to keep things short: the Celtic Britons

lived in modern-day Britain, and they were at war with Roman invaders for the

first few centuries AD. After the Romans left, the Celts were invaded and

displaced by the Anglo-Saxons, who were dominated by the Normans.

This resulted in a plethora of units of

measurement. Many Anglo-Saxon units had some basis in the people’s agricultural

past. For example, 3 barleycorns equalled 1 ynce (inch), and an acre was

considered a field the size a farmer could plough in a single day. The foot,

obviously having a connection to the length of the human appendage, was in use,

but it had various conflicting specifications.

This resulted in a plethora of units of measurement. Many Anglo-Saxon units had some basis in the people’s agricultural past. For example, 3 barleycorns equalled 1 ynce (inch), and an acre was considered a field the size a farmer could plough in a single day. The foot, obviously having a connection to the length of the human appendage, was in use, but it had various conflicting specifications.

The Norman kings brought Roman measurements to Britain, specifically the 12-inch foot and the mile, which was defined originally as the length of 1000 paces of a Roman legion. If you’d like to read more about this background, please refer to my post on the simple peg measure in Whisky vs the non-conformal Whiskey.

The metric tonne is 1000 Kg. Since 1 Kg=2.2046 lbs, one metric tonne = 2204.6 lbs.

We have left the SI or Metric System out since our discussion is on volumetric measures, but that doesn’t hide the fact

that both countries have not fully adjusted to global measures. How long will

they bask in lost memories of deluded grandeur?

The article on the UK pint vs the US pint has been taken from an ansi.org Blog post of 22/6/2018.