With each year, the number of distilleries in Scotland keeps increasing, pushing up the demand for not just single malt Scotch whiskies created in the classic mould, but also young Scotch whiskies created in a non-conformal mode. These distilleries deliver the essential requirements using advanced concepts, people-fuelled ideas and crowd-sourced funds. This is the third post on new distilleries and I recommend that you read the first two that are posted as disparate and complete articles. You may read the first post of 2019 at this link and its sequel of just a year ago, 2021, at this link. The two posts referred to are also interlinked. What do 2022-23 have in store for us? Read on...

WOLFCRAIG DISTILLERY

Wolfcraig will be a world-class, succinctly

21st-century distillery built on rich expertise. It will blend tradition and modern innovation to create the perfect malt. Incremental improvements will be

made across the distillation process to ensure perfection of product in all malt and premium spirit lines.

It will be born of a rich heritage but will aim to evolve the traditional distillery models to create a distinctly contemporary product.

Wolfcraig will introduce pioneering blockchain

technology throughout its supply chain. The highest standard in providing

strict supervision and safeguarding, blockchain will ensure immutable

monitoring and proof of provenance, and authenticity for both the craft and

product – from barley to bottle – driving value.

This guarantee of Wolfcraig authenticity will be easily

accessed on their labelling through simple QR codes.

Heritage

Wolfcraig will be built upon traditional skills, proud

heritage, environmental innovation but with a contemporary vision.

The architecture of the Distillery will echo the ethos

of the product – Proud Heritage, Cutting Edge Vision. The founders have worked

closely with the landowner and the local council planning department to ensure

the building becomes part of its natural environment.

Working with Forsyths of Rothes, the gold standard for

distillation engineering, Wolfcraig will become one of the nation’s largest

boutique distilleries, with the capacity to produce 1.5 million litres of

alcohol annually.

The Legend

Legend has it that Norse invaders looked set to attack

a small garrison of Celts who had settled on the banks of the wild Forth River.

As they crept through the cover of night, one stumbling Norseman trod on the

paw of a wolf-cub who, startled from slumber, howled for his mother who in turn

sounded the alarm for her mate.

The howls of the pack wakened the sleeping garrison who

called their men to battle and fought to save their position on the rock. The

Vikings fled both the men and the beasts, and in honour of their glorious and

unexpected victory, Wolfcraig takes its name from the courageous heart of a

wolf cub. The inspiration that runs through the very foundations of this

Distillery today.

Moving forward again in the chapters of our nation’s

rich history, Modern Scotland itself was born on the banks of the Forth through

the storm and steel of patriotic figureheads such as Robert the Bruce. Where

better to build a home for Wolfcraig… As a nod to the history and legend which

surrounds Stirling, Wolfcraig Distillery will bring these legends back to life,

through the Wolfcraig Single Malt Expressions, with each Expression inspired by

iconic Scottish heroes.

The distillery

Wolfcraig Distillery is passionate about Scotch Whisky

and has great plans for it’s future. The company is led by globally recognised

industry experts and includes 4 Masters of the Quaich.

These experts share the vision of creating 21st century

distillery in the heart of Scotland that aims to disrupt the traditional

distillery model by infusing rich heritage with digital technologies created

specifically to ensure provenance and authenticity. Wolfcraig aims to redefine

the placing of Scotch in the traditional whisky market whilst securing its

place in the fast growing consumer market for generations to come.

Sustainability

Long term success will depend upon the conservation of the natural environment and they will ensure that a clean, green, sustainable business model is at the core of building their legacy.

Wolfcraig will lead by example with environmental innovation and best practice, ensuring that all areas of production and business administration use renewable sources where possible. The objective is to create a carbon-free distillery from the outset.

In addition, the team will work closely with Zero Waste

Scotland and their Circular Economy Team, to ensure that all by-products will

be recycled in sustainable industries.

UPDATE

In Stirling, the team behind Wolfcraig Distillery has announced that the facility will now be constructed at the Craigforth Campus in the city. The £15m distillery and visitor centre was due to be built on the outskirts of the city but plans were changed since the new location has better links to public transport and is much closer to the heart of Stirling, making it easier for visitors and tourists to access the distillery. Craigforth Campus is on the site of the former Prudential headquarters and is being redeveloped by property firm Ambassador Group.

St Boswells Distillery

100% Scottish Spirit: First and only grain whisky

distillery in the Scottish Borders.

|

| ARCHITECURAL RENDERING OF THE DISTILLERY |

Jackson Distillers has submitted plans for a £45 million distillery in the Scottish Borders named Boswells Distillery, which will produce grain whisky for the blending industry and grain neutral spirit for gin and vodka production.

The distillery, born out of Charlesfield Farm in the

Scottish Borders, will be the first, and only Scottish Borders based producer

of single grain whisky spirit and grain neutral spirit using 100% Scottish

water and cereals of proven traceable origin. The company – which includes

former Glenmorangie and Diageo executives – claims the state-of-the-art

facility will be the lowest carbon and most resource-efficient grain distillery

in Scotland, capable of producing 20 million litres of pure alcohol a year.

As an independent, the distillery’s No.1 priority is to

supply grain spirit to independent distilleries, to relieve doubt about supply.

The primary product from the distillery will be a quality Scotch Grain Whisky

perfect for use in Premium Blended Scotch Whiskies. The spirit will be produced

using fully traceable Scottish grown barley and wheat.

A small volume of new make spirit will be laid down in

a variety of high quality casks to produce a range of Single Grain brands. The

distillery will also produce a premium low methanol Grain Neutral Spirit (GNS)

for use in all white spirit drinks. The GNS will also only use fully traceable

Scottish cereals, ideal for the growing Scottish Gin market.

The distillery is designed to have the capability to

run campaigns of a variety of Scottish cereals.

This will enable them to offer spirit produced from rye, oats or other

grains. They will also be certified to produce organic and kosher spirits. As an independent, they can be flexible to

produce what customers demand. The distillery will produce two by-products:

distillers syrup and draff, both ideal for use as feedstock for anaerobic

digestion and as animal feed.

Charlesfield Industrial Estate in the heart of the

Scottish Borders is the ideal location. The new distillery will be sited on

land at Charlesfield, St Boswells, near Melrose. It will create new jobs and

utilise their own renewable energy. The proximity to the production areas of

wheat and barley shortens the distance of travel for the raw materials, keeping

haulage and carbon costs down, and the easy access to the trunk road network to

the north and south allows the spirit access to markets not just in Scotland

but in the rest of the UK.

The availability of space to create warehousing will

allow cost effective maturation of the spirit on site for our own spirit and

also allows customers to purchase product for storage and maturation at JDL.

The venture brings significant benefits to the local

Scottish Borders economy by using local suppliers for grain, providing new

employment opportunities, and it will do so with minimal impact on the

environment through recycling production by-products such as spent lees (to be

used in the adjacent AD plant, and for use as cattle feed to local farmers),

and where possible recycling water used in the distillation process. The main

supply of water for the distillery will come from a spring that will be bored

on land which will form part of the distillery ground, with the bore hole

perfectly situated under the mash house.

To ensure the distillery produces consistent

high-quality spirits, they will make sure all processes from cereal purchasing

to distillation follow a number of standards and controls. All cereals will be

only purchased from farms which are members of the Scottish Quality Cereals

Association. This will ensure fully traceability on key ingredients.

Plans for the site – at Charlesfield Industrial Estate in Melrose – are under consideration by Scottish Borders Council.

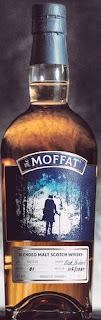

Moffat Distillery

|

| EARLY DAYS |

In 2006 Thai company Pacific Spirits, part of the Great Oriole Group, soon to be known as Thaibev, acquired Inver House Distillers, a US drinks company that had built the Moffat Distilleries complex three miles from Airdrie. These distilleries were shuttered by 1986. Only Inver House office complexes remain.

Dark Sky Spirits was granted planning permission on 27 Jan 2020 to build its whisky distillery in the Scottish town of Moffat. There is no connection with Thaibev. At the Moffat site, Dark Sky Spirits plans to construct a distillery and visitor centre, which is expected to entice up to 9,000 visitors in its first year. Moffat distillery will also house a retail unit and tasting rooms and will offer parking for 22 vehicles.

Dark Sky received £320,000 (US$415,000) in funding to

build the facility. The investment will be used to construct the distillery and

a bonded warehouse, which will help reduce bottling and transportation costs,

and begin blending. Construction on the site will start later, given the

pandemic and distillation will follow. The proposed site, off Old Carlisle Road

in Moffat, will allow Dark Sky Spirits to produce 60,000 litres of pure alcohol

in its first year.

The new distillery, nestled in the hills of Moffat, is thought to be the first legal distillery to operate in Moffat. The product is named after Moffat’s status as Europe’s first dark sky town, a title awarded to Moffat due to the installation of eco-friendly street lighting that keeps light pollution to a minimum. The construction of the new site will allow the business to produce its first single malt. Dark Sky has been making The Moffat blended malt whisky off-site since 2018.

This year, Dark Sky Spirits has broken ground on the

Moffat Distillery. The new distillery, due to begin production 2022, will allow

the company to add its own single malt to its portfolio, as well as offering

tours and tastings to whisky fans.

The distillery will operate what it claims is

Scotland’s only direct wood-fired still, which will offer a signature flavour

for the whisky and create a sustainable production process, according to the

founders. Furthermore, Dark Sky Spirits plans to create a ‘makers marketplace’

on its site, a dedicated creative space for local producers to work together

and share ideas. The Dark Sky Spirits team hope to offer ‘hard hat’ tours in

late 2022, ahead of the public launch. Once open, the new site will offer tours,

tastings, workshops and a whisky bar.

Midhope Castle Distillery

Midhope Castle is a 16th-century tower house in Scotland. It is situated in the hamlet of Abercorn on the Hopetoun estate, About 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) to the west of South Queensferry, on the outskirts of Edinburgh. Midhope Castle is featured as a location in the Outlander TV series on Starz as the main character Jamie Fraser’s family home called Lallybroch but also known as Broch Tuarach.

Former Diageo director Ken Robertson and the owners of high-end whisky bottler Golden Decanters are behind plans to build a malt distillery on Hopetoun Estate near Queensferry. Robertson is listed as a director of Midhope Castle Distillery Company along with Julia Hall Mackenzie-Gilanders and Ann Medlock.

The planning application submitted by 56three Architects for a new malt distillery on the historic Hopetoun Estate at Midhope, West Lothian, on behalf of Golden Decanters, has been approved. 56three worked very closely with Rankin Fraser Landscape Architects to ensure that the new building will sit sensitively within the existing landscape setting.

Fans of Outlander flock to the site in their thousands, but can only currently visit the grounds to take pictures of the castle. Once the development is complete, these visitors will be able to access the repaired parts of the castle, which are set to be revamped to include tasting, meeting and dining rooms. Initial work is expected to be completed in 2022 with further renovation and repairs to the castle (including accommodation) to take place once the business is established.

Midhope Castle grounds will be home to a new whisky distillery. As well as building a distillery, the plans include details on restoring the castle, which is currently an empty shell, to eventually include visitor accommodation. The plans, which were approved on 13 April, show the site will include a 2850sqm distillery building, service buildings, landscaping, an access road and parking.

The Midhope Castle Distillery Company said the contemporary distillery is to be positioned within a carefully designed landscape drawing inspiration from historic features. Immediately adjacent to the distillery site is Midhope Castle, a 16th century tower house which is presently an empty shell. It is intended that the distillery development will lead to a longer-term project involving the significant restoration and return to use of Midhope Castle and its immediate grounds.

Hopetoun Estate has a long tradition of growing and supplying malting barley for the Scotch Whisky industry and the new distillery would use exclusively estate-grown barley. It would also reflect the estate’s commitment to environmental sustainability.

FIRST DISTILLERY ON ISLE OF HARRIS

Islands Single Malt Scotch Whisky

This community-focussed project led by an Anglo-American musicologist is the first commercial distillery to be built on the island of Harris.

The ‘social distillery’ is a true island distillery, run by the local community for the local community. All the cows on Harris are fed for free on the distillery’s draff; work experience placements are offered to school children during the summer; local artists’ work feature within its walls and the visitor centre plays home to book readings.

The only style of whisky fit for a distillery like this is a complex island malt, lightly peated with additional layers of flavour from a cloudy wort and long fermentations. Of course maturation takes place completely on the island, predominantly in ex-Bourbon casks with some oloroso Sherry butts.

The single malt will be bottled as The Hearach (a Harris islander), which won’t be ready for some time, but expect it to be full-bodied, fruity and with a touch of that salty, windswept Hebridean character island malts are famous for.

The first cask with 516 bottles is slated for opening late 2023, with a steady stream of bottling throughout the year. The whisky is expected to be 46 per cent ABV with an opening price of ~65£.