THE WOMEN BEHIND THE STILLS

PRODUCING ILLICIT MALT WHISKY: CARDOW

Cardhu distillery in Speyside is, upon arriving at it, like many others in the area. There are beautiful stone buildings, a large forecourt, a visitor’s centre, stills, washbacks, casks… the things one would expect to find at any whisky-making outpost in the region. But it has a most curious and unique history.

It is when you pierce below its surface to understand more of its past that you realise this was no ordinary distillery. The history of Cardhu is forever entangled with the stories of two of the sharpest, most inventive and strong-willed women in Scotland’s early whisky narrative: Helen and Elizabeth Cumming. The former laid the foundations for success while the latter built on those and took Cardhu to being one of the most important in the region.

The distillery was founded as Cardow (Gaelic for black rock) by John Cumming in the early 1800's, when he started using local peat and the barley grown in the family farm to produce his own uisge beatha.

|

|

He began as a moonshine distiller. The proximity of the river Spey was ideal for a distillery and the surrounding hills offered a hide-out in case of raids by the excise men. In 1816, John was convicted for distilling without official license three times. Distilling to small extents was usual for the farmers at that time and nearly no one cared for licenses. Cardow was distilling long before licenses to do so arrived in the valley in 1824. From about 1813, records show that John Cumming was busy taking care of the farmlands while the wily Helen was equally busy running the household and distilling the whisky. It is, therefore, not surprising, that Cardhu is accepted in history to have been the first of the Speyside distilleries to take out one of the new licences after the Excise Act was passed in 1823.

According to extracts from the insightful whisky encyclopedia by Alfred Barnard – published in 1893 – Helen was “a most remarkable character and a woman of many resources; she possessed the courage and energy of a man, and in devices and plans to evade the surveillance of the gaugers [those who hunted down illicit stills and the root of the word gauging], no man nor woman in the district could equal her.” In short: she was rather good at hiding her work from the authorities.

It was not just her ability to hide her illegal distilling that made her a famous character. It was the fact she did it with such aplomb and respect for her neighbours. Stories go that when Helen discovered the gaugers were on their way to do inspections, she would raise a red flag or hang out her washing to alert her neighbours and the prochahs, or boys who would run messages around the district, would see the signal and run to tell others. Then, she would invite the gaugers in, give them a bed for the night and wish them well on their way the next morning. You’ve got to admire her cheek!

Stories also go that she would walk all the way to Elgin – some 20 miles away – with bladders of whisky tied up underneath her skirts to sell on to willing consumers. The quality of her spirit was recognised early on so that by the time licences were being granted to distilleries such as Glenlivet (as it was known then, without its famous prefix, ‘The’), she did not need to put that name before her product, unlike many in the region which would have used Glenlivet as a prefix to give their spirit more credibility.

Helen outlived her husband by 39 years, reaching the incredibly ripe old age of 98. Not only did she run the distillery but she also managed to have eight children and 56 grandchildren.

|

But while she remained – it is said – of good mind until her death, it was her daughter-in-law who eventually took on the reins. Elizabeth was the wife of Helen’s son, Lewis, who had run the distillery in the late 1860s, increasing its output from 240 gallons a week to 500. When he died prematurely in 1872, it was Elizabeth who took up the running of the distillery.

According to Barnard: “Mrs Lewis Cumming personally conducted the business for nearly seventeen years, and to her efforts alone is the continued success of the distillery entirely due. It was this lady who enlarged the distillery in 1884, previous to which time the plant could only make 500 gallons per week; after she had made the alterations and extensive additions the new distillery turned out 1,680 gallons. As a book-keeper and correspondent, Mrs Cumming has not, in her own sex, an equal in this country.” Actually, Elizabeth rebuilt the primitive set-up in 1884 completely, selling the old stills and waterwheel to William Grant, who was planning to build his family distillery, called Glenfiddich, in Dufftown. By then, Cardhu had established itself as a favourite of blenders, but was also available as a single malt in London as early as 1888.

Barnard had viewed the single malt barn and the kiln which were of standard description; now there are two old barns and kilns but they have not been used as such since 1968 when malt barn no. 2 was converted into a warehouse.

The original mill was powered by a large 18 feet diameter waterwheel, presumably powered by the Cardow Burn that feeds a small dam beside the site and a larger one further upstream. The process water was and still is piped over two miles from a spring on Mannoch Hill, yet another distillery making use of this important watershed. I’m going to have to take a proper count of the number of distilleries that rely on Mannoch for water in one form or another - it may be more than Benrinnes and perhaps more than any other hill in Scotland since the Campbeltown heydays when Beinn Ghuilean was the filter for the waters of Crosshill Loch. The peat used at Cardow was also cut from moss land on Mannoch Hill but today the malt is almost unpeated.

The mash tun was originally quite small at just 12 feet wide by 5 feet deep and there were 6 washbacks holding 18,200 litres each. The current tun is a much larger stainless steel full lauter vessel that produces 35,000 litres of worts per mash to fill into one of the ten washbacks, eight of Douglas fir and two of stainless steel. Fermentation is a fairly regulation 72 hours.

The stills were quite small at first, 9,100 litres for the wash still and 7,300 litres for the spirit, and the spirit was condensed in a cement worm tub that no longer exists. There were two more stills added (together with a larger mash tun and new washbacks) in 1899 and a further two in 1960. The wash stills now take a 17,375 litre charge and the spirit stills 14,780 litres. The lyne arms on the wash stills are horizontal but they rise very slightly on the spirit stills to create a lighter, yet still oily spirit that is condensed in internally placed shell and tube condensers.

The new distillery was capable of producing 273,000 litres p.a. but working to 182,000 litres at the time, compared to 114,000 litres p.a. at the old farm distillery. The capacity of those six stills is now 3.2m litres placing Cardhu inside the top 50% in Scotland by volume. Only bourbon casks are used for the 12yo single malt but some of the production is matured in sherry casks, all intended for blending. There are around 7,500 casks in five dunnage warehouses around the site but most of the production is for blending and is stored in central bonds. There is a dedication stone on the front of warehouse no.7 inscribed ‘E.C. 1884’ in recognition of the founding of the new site by Elizabeth Cumming.

Barnard’s reporting of Cardow doesn’t stop there though. He returned to the distillery around seven or eight years later as part of his research for a chapter in a pamphlet he wrote for John Walker & Sons Ltd which also included reports on their Kilmarnock operations and Annandale Distillery that they took over soon after buying Cardow. In 1893 Elizabeth made a very important decision: She sold Cardow to John Walker & Sons for 20,500 pounds and ensured her family shareholding in Walker’s company. She died one year later and didn’t have the chance to see the success of her wise decision: Under the shield of the big company Cardow could stand the hard times caused by the whisky market crash in 1898.

The Cardow sale to John Walker & Sons Ltd. in Sept. 1893 and Barnard's mention that it was quite recent dates his journey soon after. He also mentions that Elizabeth Cumming had retired from the distillery but still retains the house and farm, and her son John had taken over as manager and also appointed as a Director of John Walker & Sons. Elizabeth died in May 1894 so this dates Barnard’s second visit to late 93/early 94.

At that time, the distillery would have been selling most of its product on to blenders, one of which was Alexander Walker, from John Walker & Sons. In the late 1800s, the distillery was purchased by the blending house, one of the first malt distilleries in its portfolio.

Elizabeth did not simply walk away from the business that she and her mother-in-law had so faithfully built up. Instead, she ensured that her son – John Cumming – became a board member, while she continued living on the estate. She also made certain all of the distillery workers kept their jobs and that electricity was brought to the area – one of the first places to do so in the Spey Valley.

More than 120 years later, the distillery is owned by Diageo, which of course, in turn owns Johnnie Walker. It is now the ‘home’ of Johnnie Walker, with an impressive corporate hospitality area incorporating the brand’s history. Its output has also increased substantially – to 3.3 million litres per annum – but without the work and foundations laid by these two whisky women it wouldn’t have become the place it is.

|

| The Single Malt and the Blended Malt |

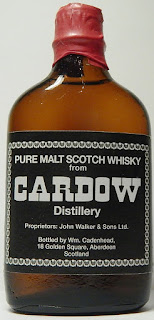

An alternative spelling to the distillery name, Cardhu, emerged

after the Second World War, when it the distillery start promoting

single malt bottlings. The distillery was formally registrated as Cardhu

Distillery in 1981.

About 30% of the production is sold as single malt, the remaining entering in blends, most significantly of Johnnie Walkers blends,

Red, Black, Green and Blue labels. The whisky fell victim to its own

success, when Diageo (the current owners) decided to introduce a vatted

malt, Cardhu Pure Malt, (augmented by other single malts of the Diageo group), as it was not able satisfy all the demand for Cardhu single malt.

|

|

|

However in 2006 Cardhu recommenced producing a single malt. The Cardhu single malt bottlings are distinguished by their smooth, delicate, easy drinking character. Versions of over 12 years old demonstrate more fat texture and caramelised nuttiness, that makes them a good match to desserts. More of Cardhu Single Malts, 12/15/18 YOs are entering the market in keeping with common economic sense. The quality of the cheaper blends are declining.

In 2018, Diageo started to implement plans to spend £150m on upgrading tourism facilities across Scotland, including a new brand home for Johnnie Walker in Edinburgh. Whisky from Diageo’s distilleries all over Scotland contribute to Johnnie Walker, but four distilleries, Glenkinchie, Cardhu, Caol Ila and Clynelish, will be linked directly to the Johnnie Walker venue in Edinburgh, representing the ‘four corners of Scotland’ and the regional flavour variations of Lowland (Glenkinchie), Speyside (Cardhu), Island (Caol Ila) and Highland (Clynelish) crucial to the art of whisky blending. Together this will create a unique Johnnie Walker tour of Scotland, encouraging visitors to the capital city to also travel to the country’s extraordinary rural communities. Cardhu’s upgrade, with scenic access and an orchard planted to highlight the history of the distillery, will reflect the influence of Helen and Elizabeth Cumming.

In the stonework of that calm outlook, the tranquility and the enduring cheek of that distillery – there is a stuffed lion toy that gets placed in random parts of the distillery so look out for it if you

visit – you can feel the ghosts of these women. And, in my personal

belief, it is all the more enriched for it.